Chemical Bonding and Molecular Structure

MODULE 2: CHEMICAL BONDING AND MOLECULAR STRUCTURE

Topic: Hybridization and Shapes of Simple Molecules (VSEPR Theory and Molecular Geometry)

1. INTRODUCTION

Chemical bonding and molecular geometry are fundamental

concepts that explain how atoms combine to form molecules and why

molecules have specific shapes.

The shape of a molecule determines many of its physical and chemical

properties—such as boiling point, polarity, biological activity, and even

drug-receptor interaction in medicine.

2. VALENCE SHELL ELECTRON PAIR REPULSION (VSEPR) THEORY

What Is VSEPR Theory?

The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion Theory, abbreviated as VSEPR theory, is based on the premise that there is a repulsion between the pairs of valence electrons in all atoms, and the atoms will always tend to arrange themselves in a manner in which this electron pair repulsion is minimalised. This arrangement of the atom determines the geometry of the resulting molecule.

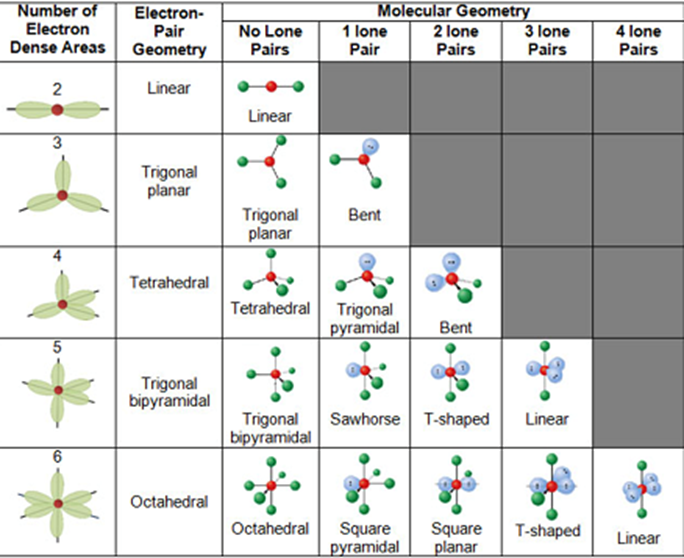

The different geometries that molecules can assume in accordance with the VSEPR theory can be seen in the illustration provided below.

VSEPR Theory – Different Geometries That Molecules Can Assume

The two primary founders of the VSEPR theory are Ronald Nyholm and Ronald Gillespie. This theory is also known as the Gillespie-Nyholm theory to honour these chemists.

3. KEY POSTULATES OF VSEPR THEORY

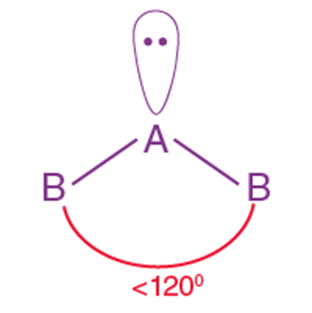

- The shape of a molecule depends on the number of bonding pairs and lone pairs of electrons around the central atom.

- Electron pairs repel each other due to their negative charges.

- The

repulsion follows the order:

Lone pair–Lone pair > Lone pair–Bond pair > Bond pair–Bond pair. - The geometry adopted minimizes these repulsions.

Limitations of VSEPR Theory

Some significant limitations of the VSEPR theory include

- This theory fails to explain isoelectronic species (i.e., elements having the same number of electrons). The species may vary in shape, despite having the same number of electrons.

- The VSEPR theory does not shed any light on the compounds of transition metals. The structure of several such compounds cannot be correctly described by this theory. This is because the VSEPR theory does not take into account the associated sizes of the substituent groups and the lone pairs that are inactive.

- Another limitation of the VSEPR theory is that it predicts that halides of group 2 elements will have a linear structure, whereas their actual structure is a bent one.

4. TYPES OF MOLECULAR SHAPES AND EXAMPLES

|

No. of Electron Pairs |

Shape |

Bond Angle |

Examples |

|

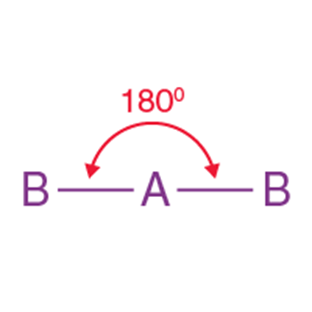

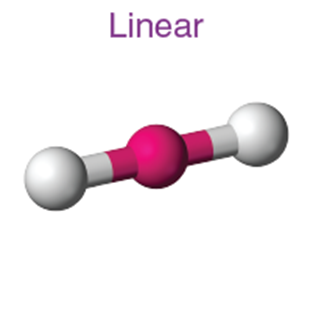

2 |

Linear |

180° |

BeCl₂, CO₂ |

|

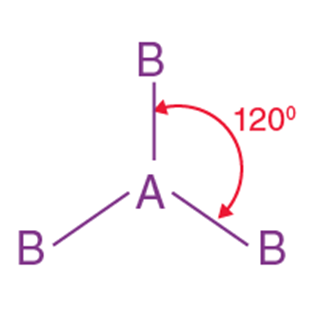

3 |

Trigonal planar |

120° |

BF₃, SO₃ |

|

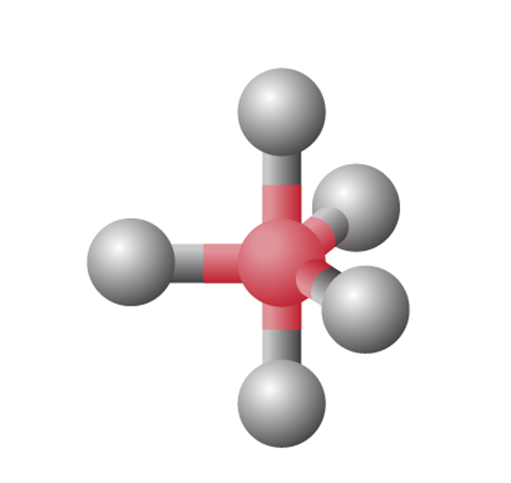

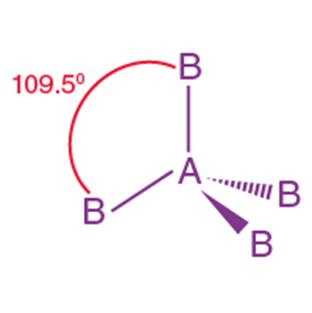

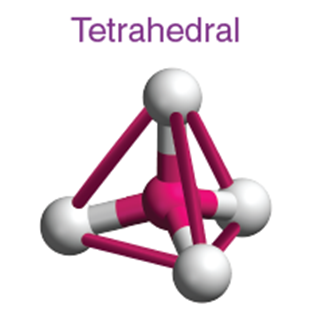

4 |

Tetrahedral |

109.5° |

CH₄, NH₄⁺ |

|

5 |

Trigonal bipyramidal |

120° and 90° |

PCl₅ |

|

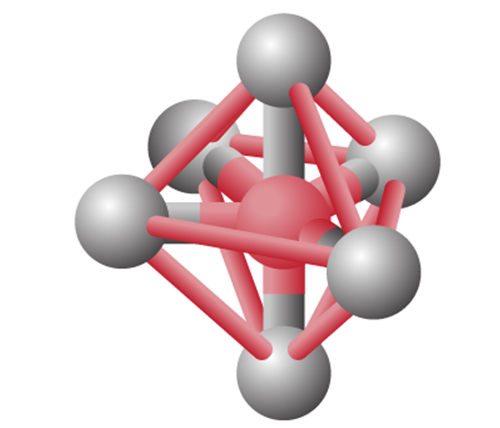

6 |

Octahedral |

90° |

SF₆ |

|

3 (with 1 lone pair) |

Bent (angular) |

~118° |

SO₂ |

|

4 (with 1 lone pair) |

Trigonal pyramidal |

~107° |

NH₃ |

|

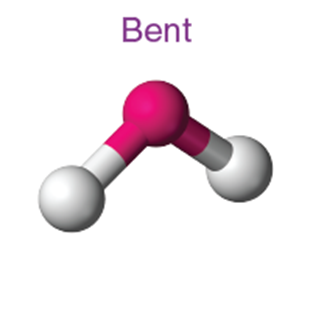

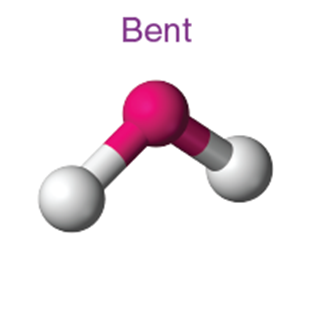

4 (with 2 lone pairs) |

Bent (angular) |

~104.5° |

H₂O |

Geometry of some covalent molecules based on VSEPR theory

|

Molecular Type |

No. of bond pairs |

No. of lone pairs |

Geometry of molecule |

Shape of the molecule |

Examples |

|

AB2 |

2 |

0 |

Linear |

|

|

|

AB3 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

AB2L |

2 |

1 |

|

|

SO2 |

|

AB4 |

4 |

0 |

|

|

|

7. HYBRIDIZATION THEORY

Definition:

Hybridization, in Chemistry, is defined as the concept of mixing two atomic orbitals to give rise to a new type of hybridized orbitals (called hybrid orbitals). This intermixing usually results in the formation of hybrid orbitals having entirely different energy, shapes, etc. The atomic orbitals of the same energy level mainly take part in hybridization. However, both fully-filled and half-filled orbitals can also take part in this process, provided they have equal energy. During the process of hybridization, the atomic orbitals of comparable energies are mixed together and mostly involves the merging of two ‘s’ orbitals or two ‘p’ orbitals or the mixing of an ‘s’ orbital with a ‘p’ orbital, as well as ‘s’ orbital with a ‘d’ orbital. The new orbitals, thus formed, are known as hybrid orbitals. More significantly, hybrid orbitals are quite useful in explaining atomic bonding properties and molecular geometry.

Key Features of Hybridization

- Atomic orbitals with equal energies undergo hybridization.

- The number of hybrid orbitals formed is equal to the number of atomic orbitals mixed.

- It is not necessary that all the half-filled orbitals must participate in hybridization. Even completely filled orbitals with slightly different energies can also participate.

- Hybridization happens only during the bond formation and not in an isolated gaseous atom.

- The shape of the molecule can be predicted if the hybridization of the molecule is known.

- The bigger lobe of the hybrid orbital always has a positive sign, while the smaller lobe on the opposite side has a negative sign.

8. TYPES OF HYBRIDIZATION AND EXAMPLES

|

Type |

Orbitals Involved |

Shape |

Examples |

Bond Angle |

|

sp |

1 s + 1 p |

Linear |

BeCl₂, CO₂ |

180° |

|

sp² |

1 s + 2 p |

Trigonal planar |

BF₃, C₂H₄ |

120° |

|

sp³ |

1 s + 3 p |

Tetrahedral |

CH₄, NH₃, H₂O |

109.5° |

|

sp³d |

1 s + 3 p + 1 d |

Trigonal bipyramidal |

PCl₅ |

120° & 90° |

|

sp³d² |

1 s + 3 p + 2 d |

Octahedral |

SF₆ |

90° |

Types of Hybridization

Based on the types of orbitals involved in mixing, the hybridization can be classified as sp3, sp2, sp, sp3d, sp3d2 and sp3d3. Let us now discuss the various types of hybridization, along with their examples.

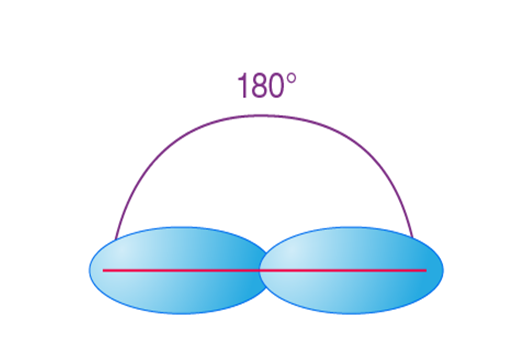

sp hybridization is observed when one s and one p orbital in the same main shell of an atom mix to form two new equivalent orbitals. The new orbitals formed are called sp hybridized orbitals. It forms linear molecules with an angle of 180°.

- This type of hybridization involves the mixing of one ‘s’ orbital and one ‘p’ orbital of equal energy to give a new hybrid orbital known as an sp hybridized orbital.

- The sp hybridization is also called diagonal hybridization.

- Each sp hybridized orbital has an equal amount of s and p characters – 50% s and 50% p characters.

Examples of sp Hybridization:

- All compounds of beryllium, like BeF2, BeH2, BeCl2

- All compounds of a carbon-containing triple bond, like C2H2.

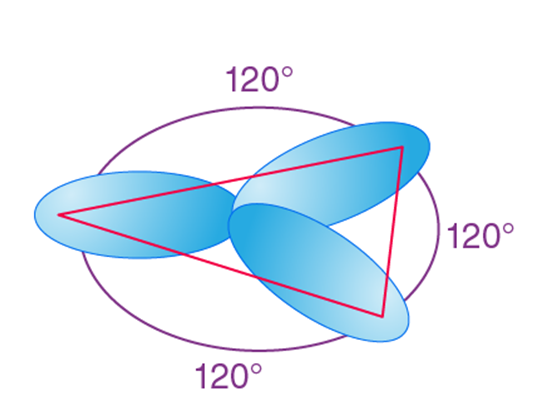

sp2 hybridization is observed when one s and two p orbitals of the same shell of an atom mix to form 3 equivalent orbitals. The new orbitals formed are called sp2 hybrid orbitals.

- sp2 hybridization is also called trigonal hybridization.

- It involves the mixing of one ‘s’ orbital and two ‘p’ orbitals of equal energy to give a new hybrid orbital known as sp2.

- A mixture of s and p orbital formed in trigonal symmetry and is maintained at 1200.

- All three hybrid orbitals remain in one plane and make an angle of 120° with one another. Each of the hybrid orbitals formed has a 33.33% ‘s’ character and 66.66% ‘p’ character.

- The molecules in which the central atom is linked to 3 atoms and is sp2 hybridized have a triangular planar shape.

Examples of sp2 Hybridization

- All the compounds of Boron, i.e., BF3 and BH3

- All the compounds of carbon, containing a carbon-carbon double bond, Ethylene (C2H4)

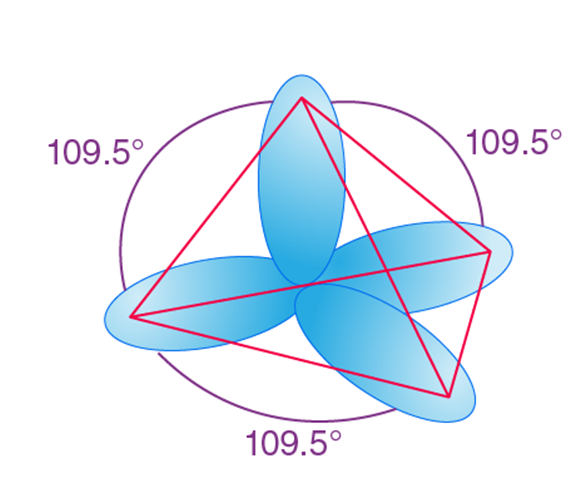

When one ‘s’ orbital and 3 ‘p’ orbitals belonging to the same shell of an atom mix together to form four new equivalent orbitals, the type of hybridization is called a tetrahedral hybridization or sp3. The new orbitals formed are called sp3 hybrid orbitals.

- These are directed towards the four corners of a regular tetrahedron and make an angle of 109°28’ with one another.

- The angle between the sp3 hybrid orbitals is 109.280

- Each sp3 hybrid orbital has 25% s character and 75% p character.

- Examples of sp3 hybridization are ethane (C2H6) and methane.

sp3d Hybridization

sp3d hybridization involves the mixing of 1s orbital, 3p orbitals and 1d orbital to form 5 sp3d hybridized orbitals of equal energy. They have trigonal bipyramidal geometry.

- The mixture of s, p and d orbital forms trigonal bipyramidal symmetry.

- Three hybrid orbitals lie in the horizontal plane inclined at an angle of 120° to each other, known as the equatorial orbitals.

- The remaining two orbitals lie in the vertical plane at 90 degrees plane of the equatorial orbitals, known as axial orbitals.

- Example: Hybridization in phosphorus pentachloride (PCl5)

sp3d2 Hybridization

- sp3d2 hybridization has 1s, 3p and 2d orbitals, that undergo intermixing to form 6 identical sp3d2 hybrid orbitals.

- These 6 orbitals are directed towards the corners of an octahedron.

- They are inclined at an angle of 90 degrees to one another.

9. APPLICATION OF HYBRIDIZATION IN MEDICINE

- Carbon’s sp³ hybridization in organic molecules forms the backbone of biomolecules like proteins, lipids, and DNA.

- sp² hybridized carbon in double bonds contributes to unsaturated fats, affecting cholesterol metabolism.

- sp hybridized atoms in molecules like ethyne (acetylene) are found in anesthetic derivatives and pharmaceutical synthons.

10. COMBINING VSEPR AND HYBRIDIZATION

|

Molecule |

Central Atom Hybridization |

Shape (VSEPR) |

Bond Angle |

|

BeCl₂ |

sp |

Linear |

180° |

|

BF₃ |

sp² |

Trigonal planar |

120° |

|

CH₄ |

sp³ |

Tetrahedral |

109.5° |

|

NH₃ |

sp³ |

Trigonal pyramidal |

107° |

|

H₂O |

sp³ |

Bent |

104.5° |

|

PCl₅ |

sp³d |

Trigonal bipyramidal |

90° & 120° |

|

SF₆ |

sp³d² |

Octahedral |

90° |

11. SUMMARY

- VSEPR Theory explains why molecules adopt particular shapes.

- Hybridization Theory explains how orbitals mix to form those shapes.

- Shape influences properties, such as polarity, solubility, reactivity, and biological activity.

- In medicine, understanding molecular geometry is crucial for drug design, enzyme activity, and biomolecular interactions.

12. QUICK CHECK QUESTIONS

- What determines the shape of a molecule according to VSEPR theory?

- Why is the H₂O molecule bent rather than linear?

- Which type of hybridization is present in methane (CH₄)?

- Give one example each of sp² and sp³ hybridized molecules.

- How does molecular geometry affect drug-receptor interactions?

CHEMICAL BONDING AND MOLECULAR STRUCTURE

Topic: Valence Forces – Types of Chemical Bonding (Ionic, Covalent, and Metallic Bonds)

1. INTRODUCTION

All substances around us—whether metals, salts, or

biological molecules—are held together by chemical bonds.

A chemical bond is the force of attraction that holds atoms or ions

together in compounds.

These forces arise because atoms seek stability, often by achieving a full outer shell of electrons (noble gas configuration).

2. WHY ATOMS FORM BONDS

Atoms form bonds to:

- Achieve greater stability (lower energy state).

- Attain a full valence shell (usually 8 electrons – the octet rule).

- Form new substances with different physical and chemical properties.

3. TYPES OF CHEMICAL BONDS (VALENCE FORCES)

|

Type of Bond |

Mode of Formation |

Nature of Attraction |

Typical Examples |

|

Ionic bond |

Transfer of electrons |

Electrostatic attraction between positive and negative ions |

NaCl, KBr, CaCl₂ |

|

Covalent bond |

Sharing of electrons |

Mutual sharing of valence electrons |

H₂O, CO₂, CH₄, O₂ |

|

Metallic bond |

Sea of delocalized electrons |

Attraction between metal cations and free-moving electrons |

Cu, Fe, Zn, Al |

A. IONIC BONDING

Definition:

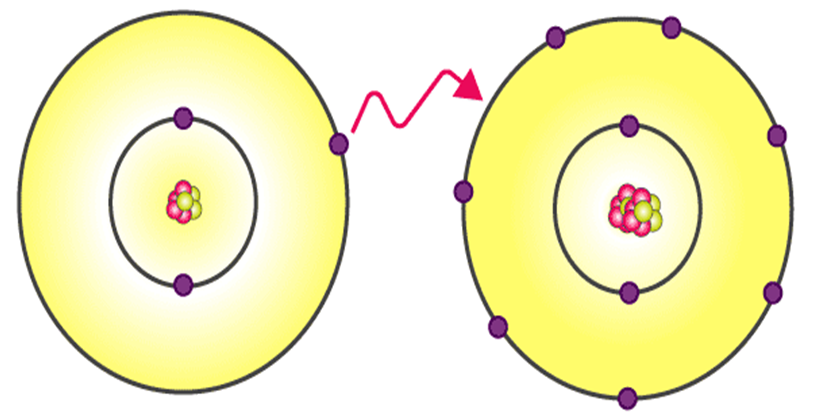

An ionic bond is formed when one atom transfers electrons to another atom, resulting in oppositely charged ions (cations and anions) that attract each other by electrostatic force.

Example:

Formation of sodium chloride (NaCl)

Characteristics of Ionic Compounds

- High melting and boiling points (strong electrostatic forces).

- Soluble in water (polar solvent).

- Conduct electricity in molten or aqueous form (ions are mobile).

- Usually crystalline solids.

Medical Examples:

- Ionic compounds like NaCl (table salt) are electrolytes in the body, helping nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction.

- Calcium phosphate (Ca₃(PO₄)₂), an ionic compound, strengthens bones and teeth.

- Electrolyte imbalance (e.g., loss of Na⁺, K⁺, or Cl⁻) affects heart rhythm and muscle function.

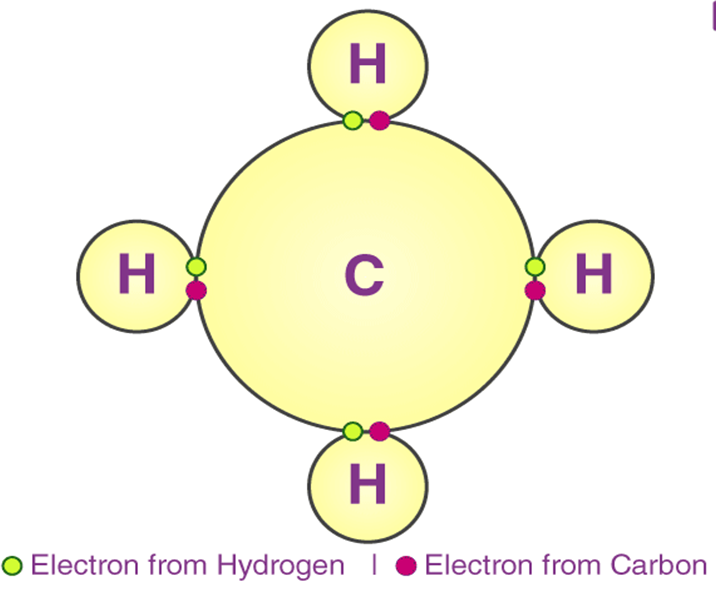

B. COVALENT BONDING

Definition:

A covalent bond forms when two atoms share one or more pairs of electrons to achieve stability.

Example:

Formation of hydrogen molecule:

H⋅+⋅H → HH

Each hydrogen atom contributes one electron to form a shared pair.

Nature of covalent bonds

Covalent bonds can be either polar or non-polar in nature. In polar covalent chemical bonding, electrons are shared unequally since the more electronegative atom pulls the electron pair closer to itself and away from the less electronegative atom. Water is an example of such a polar molecule.

A difference in charge arises in different areas of the atom due to the uneven spacing of the electrons between the atoms. One end of the molecule tends to be partially positively charged, and the other end tends to be partially negatively charged.

Types of Covalent Bonds

|

Type |

Electron Pairs Shared |

Example |

|

Single bond |

1 pair (2 e⁻) |

H–H (H₂), CH₄ |

|

Double bond |

2 pairs (4 e⁻) |

O=O (O₂), CO₂ |

|

Triple bond |

3 pairs (6 e⁻) |

N≡N (N₂), C₂H₂ |

Characteristics of Covalent Compounds

- Usually gases or liquids with low melting and boiling points.

- Do not conduct electricity (no free ions).

- Insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents.

- Bonds are directional (specific shape).

Examples:

- Most biological molecules (proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids) are covalently bonded.

- C–C, C–H, and C–O bonds form the backbone of organic and biochemical structures.

- Covalent bonds hold together DNA base pairs and amino acids in proteins.

- Drugs often rely on covalent interactions for binding to receptors or enzymes.

C. METALLIC BONDING

Definition:

A metallic bond is formed when metal atoms release their valence electrons into a “sea of delocalized electrons” which move freely around positive metal ions.

This free electron movement explains the unique physical properties of metals.

Characteristics of Metallic Bonds

- Good electrical and thermal conductivity (due to mobile electrons).

- Malleable and ductile (layers of atoms can slide without breaking bonds).

- Lustrous (shiny) surface due to interaction with light.

- Variable melting points.

Example:

- Copper (Cu) and iron (Fe) are metallic elements used in medical instruments and hemoglobin formation (Fe²⁺ in blood).

- Titanium and stainless steel alloys (metallic bonds) are used in surgical implants and prosthetics due to strength and flexibility.

- Metallic bonding also explains heat conduction in surgical tools, allowing quick sterilization.

4. COMPARISON OF THE THREE TYPES OF BONDS

|

Property |

Ionic Bond |

Covalent Bond |

Metallic Bond |

|

Mode of formation |

Transfer of electrons |

Sharing of electrons |

Sea of electrons |

|

Bond strength |

Strong |

Variable |

Strong |

|

Electrical conductivity |

Only in molten/solution |

Non-conductors |

Conductors |

|

Melting/boiling points |

High |

Low to moderate |

Variable |

|

State at room temp |

Solid (crystals) |

Gases/liquids/solids |

Solids |

|

Solubility |

Soluble in water |

Insoluble |

Insoluble |

|

Examples |

NaCl, KBr, CaCl₂ |

H₂O, CO₂, CH₄ |

Fe, Cu, Zn |

|

Medical relevance |

Electrolytes, bones |

Biomolecules, drugs |

Surgical metals |

Difference Between Ionic bond, Covalent bond, and Metallic bond

To make you understand how Ionic, covalent and metallic bonds are different from each other, here are some of the major differences between Ionic, covalent and metallic bonds:

|

IONIC BOND |

COVALENT BOND |

METALLIC BOND |

|

Occurs during the transfer of electrons |

Occurs when 2 atoms share their valence electrons |

The attraction of metal cations/atoms and delocalized electrons |

|

Binding energy is higher than the metallic bond |

Binding energy is higher than the metallic bond |

Binding energy is less than covalent and ionic bond |

|

Low conductivity |

Very low conductivity |

Has high electrical conductivity |

|

Non-directional bond |

Directional bond |

Non-directional bond |

|

Present only in one state: solid-state |

Present only in all 3 states: solid, liquid, gases |

Present only in one state: solid-state |

|

Non-malleable |

Non-malleable |

Malleable |

|

Higher melting point |

Lower melting point |

High melting point |

|

Non-ductile |

Non-ductile |

Ductile |

|

Higher boiling point |

Lower boiling point |

High boiling point |

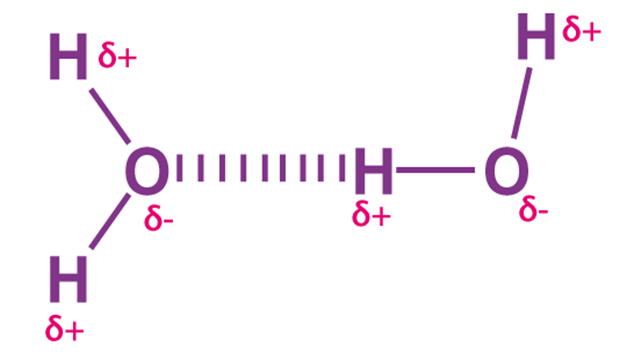

Hydrogen Bonding

Compared to ionic and covalent bonding, Hydrogen bonding is a weaker form of chemical bonding. It is a type of polar covalent bonding between oxygen and hydrogen, wherein the hydrogen develops a partial positive charge. This implies that the electrons are pulled closer to the more electronegative oxygen atom.

This creates a tendency for the hydrogen to be attracted towards the negative charges of any neighbouring atom. This type of chemical bonding is called a hydrogen bond and is responsible for many of the properties exhibited by water.

Hydrogen bonding in water

Summary of the differences between the types of bonds

|

Feature |

Hydrogen Bond |

Covalent Bond |

Ionic Bond |

Metallic Bond |

|

Type |

Intermolecular force |

Intramolecular |

Intramolecular |

Intramolecular |

|

Electron behavior |

Attraction between dipoles |

Shared electrons |

Transferred electrons |

Delocalized electrons |

|

Strength |

Moderate |

Strong |

Very strong |

Variable |

|

Example |

Between H₂O molecules |

H–O in H₂O |

NaCl |

Cu, Fe |

|

Main role |

Holds molecules together |

Holds atoms together |

Holds ions together |

Holds metal atoms together |

6. SUMMARY

- Chemical bonds (valence forces) hold atoms together in molecules and compounds.

- Ionic bonds involve transfer of electrons.

- Covalent bonds involve sharing of electrons.

- Metallic bonds involve free movement of electrons.

- The type of bonding determines the properties (melting point, solubility, conductivity).

- Understanding these helps explain how drugs, electrolytes, and biomolecules behave in the body.

7. SELF-ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS

- What is the main difference between ionic and covalent bonding?

- Explain why NaCl conducts electricity in aqueous solution but not in solid state.

- Give two examples of metallic bonding and their medical applications.

- Describe covalent bonding using water (H₂O) as an example.

- Which type of bond exists in hemoglobin, and why is it important?

STRUCTURE OF SOLIDS

1. INTRODUCTION

All matter exists in three main physical states — solid,

liquid, and gas.

Among these, solids have a definite shape and volume because

their particles are closely packed together.

However, solids are not all the same — some have ordered structures (crystals), while others are disordered (amorphous).

2. TYPES OF SOLIDS

Solids can broadly be classified into two types based on how their particles are arranged:

|

Type of Solid |

Arrangement |

Examples |

Features |

|

Crystalline Solids |

Regular, repeating arrangement of atoms, ions, or molecules (long-range order) |

NaCl, diamond, quartz |

Sharp melting point, definite shape |

|

Amorphous Solids |

Irregular, random arrangement (short-range order only) |

Glass, plastic, rubber |

No sharp melting point, soften gradually |

3. CRYSTALLINE SOLIDS

A crystal is a solid in which the constituent particles (atoms, ions, or molecules) are arranged in a definite, repeating pattern in three-dimensional space.

This arrangement forms a crystal lattice — a 3D pattern of points that show how particles are positioned.

4. TYPES OF CRYSTALLINE SOLIDS (BASED ON BONDING FORCES)

Crystalline solids are categorized by the type of bonding (interparticle forces) that holds them together:

|

Type of Crystalline Solid |

Constituent Particles |

Type of Bonding |

Examples |

Properties |

|

Ionic Solids |

Positive and negative ions |

Ionic bonds |

NaCl, KBr, CaF₂ |

Hard, brittle, high melting point, conduct electricity when molten or in solution |

|

Covalent (Network) Solids |

Atoms linked by covalent bonds |

Covalent bonds |

Diamond, SiO₂ (quartz), graphite |

Very hard (except graphite), high melting points, non-conductors (except graphite) |

|

Metallic Solids |

Positive metal ions in a sea of electrons |

Metallic bonds |

Cu, Fe, Zn |

Good conductors, malleable, lustrous |

|

Molecular Solids |

Molecules held by weak Van der Waals or hydrogen bonds |

Intermolecular forces |

I₂, H₂O (ice), CO₂ (dry ice) |

Soft, low melting points, poor conductors |

5. TYPES OF CRYSTAL STRUCTURES

The arrangement of particles in a crystal is described by its unit cell — the smallest repeating unit that defines the structure.

Common crystal systems (based on edge lengths and angles):

|

Crystal System |

Axes (a, b, c) |

Angles (α, β, γ) |

Example |

|

Cubic |

a = b = c |

90°, 90°, 90° |

NaCl, diamond |

|

Tetragonal |

a = b ≠ c |

90°, 90°, 90° |

Tin (Sn) |

|

Orthorhombic |

a ≠ b ≠ c |

90°, 90°, 90° |

Sulphur (S) |

|

Hexagonal |

a = b ≠ c |

120°, 90°, 90° |

Graphite, Zn |

|

Monoclinic |

a ≠ b ≠ c |

90°, ≠90°, 90° |

Gypsum |

|

Triclinic |

a ≠ b ≠ c |

α ≠ β ≠ γ |

K₂Cr₂O₇ |

|

Rhombohedral (Trigonal) |

a = b = c |

α = β = γ ≠ 90° |

Calcite (CaCO₃) |

- Molecular solids (Ice): Like soft cotton balls held together gently — weak attractions, easy to melt.

7. PROPERTIES OF CRYSTALLINE MATERIALS

- Definite Melting Point: Crystalline solids have a sharp melting point (NaCl melts at 801°C).

- Anisotropy: Their physical properties (e.g., hardness, refractive index) vary with direction because of ordered structure.

- Symmetry: Crystals exhibit geometric symmetry — e.g., cubic shape of NaCl crystals.

- Cleavage: Crystals break along definite planes.

- Long-range Order: Regular arrangement of particles extends throughout the entire crystal.

8. AMORPHOUS SOLIDS

Amorphous solids have no definite structure — atoms

are randomly arranged.

They behave like supercooled liquids that have lost flow.

Examples: Glass, plastic, pitch, rubber.

Properties:

- No sharp melting point (soften over a range).

- Isotropic (same properties in all directions).

- Slowly flow under pressure (glass windows in old buildings are thicker at the bottom!).

9. MEDICAL AND BIOLOGICAL APPLICATION

- Crystalline solids are crucial in drug formulation. The crystalline form of a drug affects:

- Solubility

- Absorption rate

- Shelf stability

For instance, crystalline insulin dissolves slower than amorphous insulin, allowing controlled release in diabetic patients.

- Bone and teeth are examples of biological crystalline solids, made of hydroxyapatite (Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂) — a crystalline ionic solid giving hardness and strength.

- Kidney stones (e.g., calcium oxalate crystals) are another example of biological crystallization.

- Amorphous forms (like certain tablets and gels) enhance drug solubility and bioavailability because they dissolve faster.

10. IMPORTANCE OF CRYSTAL STRUCTURE IN MATERIAL PROPERTIES

|

Crystal Type |

Bonding |

Typical Property |

Medical/Practical Relevance |

|

Ionic |

Electrostatic |

Hard, brittle, high MP |

Salts, bone minerals |

|

Covalent |

Shared electrons |

Very hard, poor conductor |

Diamond scalpels, glass syringes |

|

Metallic |

Electron sea |

Conductors, malleable |

Surgical instruments, implants |

|

Molecular |

Van der Waals/H-bonds |

Soft, low MP |

Ice, organic drugs, creams |

11. SUMMARY

- Solids are closely packed structures with definite shape and volume.

- They can be crystalline (ordered) or amorphous (disordered).

- Crystalline solids have regular arrangements leading to sharp melting points and anisotropy.

- Amorphous solids lack order, are softer, and isotropic.

- Crystal structure directly affects the properties and applications of materials, especially in medicine and pharmaceuticals.

12. QUICK CHECK QUESTIONS

- Differentiate between crystalline and amorphous solids with examples.

- State the main types of crystalline solids and give two examples of each.

- Explain why ionic solids conduct electricity only in molten or aqueous state.

- Describe the importance of crystalline structure in drug formulation.

- Which crystal structure does NaCl possess?

- Why is diamond hard while graphite is soft, though both are made of carbon?

5. INTERMOLECULAR FORCES (IMFS)

While chemical bonds hold atoms together within

molecules, intermolecular forces hold molecules to each other.

These forces determine physical properties like boiling point, melting

point, and solubility.

A. London Dispersion Forces (Van der Waals Forces)

- Weakest of all IMFs.

- Exist between all molecules, especially nonpolar ones.

- Caused by temporary dipoles due to shifting electron clouds.

Example:

Between molecules of noble gases (He, Ne, Ar) or hydrocarbons like CH₄.

Example of

application:

In lipid membranes, dispersion forces help hold nonpolar fatty acid

tails together.

B. Dipole–Dipole Forces

- Occur between polar molecules with permanent dipoles.

- Positive end of one molecule attracts the negative end of another.

Example:

Between HCl molecules or acetone molecules.

Example of applicaion:

Like two magnets aligning — similar to how drug molecules with polar groups

align with polar sites on receptors.

C. Hydrogen Bonding

- A special, strong dipole-dipole attraction between hydrogen and O, N, or F atoms.

- Responsible for the unique properties of water, DNA, and proteins.

Example:

Between water molecules or base pairs in DNA:

A=T, G≡CA=T,\ \ G≡CA=T,

(Adenine pairs with Thymine via 2 H-bonds; Guanine with Cytosine via 3 H-bonds.)

Medical Relevance:

- Hydrogen bonds maintain DNA double-helix stability.

- Protein folding depends on hydrogen bonding between amino acid chains.

- Hydrogen bonding allows water to transport nutrients and waste in the body.

6. Effects of Bonding and Intermolecular Forces on Physical Properties

|

Property |

Influenced by |

Example / Medical Relevance |

|

Boiling Point |

Strength of IMFs |

Water has high boiling point due to H-bonding — important for body temperature regulation. |

|

Solubility |

Polarity and H-bonding |

Polar drugs dissolve in blood (aqueous); nonpolar drugs dissolve in lipids. |

|

Melting Point |

Type of bonding |

Ionic solids (e.g., NaCl) have high melting points; covalent compounds (e.g., glucose) lower. |

|

Conductivity |

Ionic and metallic bonding |

Electrolytes conduct in solution; metals conduct in implants. |

|

State of Matter |

IMFs |

Weak forces → gas (O₂); moderate → liquid (H₂O); strong → solid (NaCl). |

7. Summary of Key Ideas

|

Bond Type |

Mechanism |

Example |

Strength |

Medical Analogy |

|

Ionic |

Electron transfer |

NaCl |

Strong |

Electrolytes in blood |

|

Covalent |

Electron sharing |

H₂O, CO₂ |

Moderate |

Biomolecules (DNA, proteins) |

|

Metallic |

Electron delocalization |

Fe, Cu |

Variable |

Metal implants |

|

Hydrogen bond |

Between H and O/N/F |

H₂O, DNA |

Moderate |

DNA base pairing |

|

Dispersion |

Temporary dipoles |

CH₄ |

Weak |

Lipid membrane cohesion |

In Summary

Chemical bonding and intermolecular forces are the “invisible glue” that holds everything together — from the structure of your cells to the stability of the medicines you take. Understanding them is the foundation for biochemistry, pharmacology, and molecular medicine.

BeF2,

BeCl2

BeF2,

BeCl2 Trigonal

planar

Trigonal

planar BF3,

BCl3

BF3,

BCl3 Trigonal plane

Trigonal plane  Trigonal

planar

Trigonal

planar Tetrahedral

Tetrahedral CH4,

CCl4

CH4,

CCl4