STOICHIOMETRY AND CHEMICAL REACTIONS

Module 3: STOICHIOMETRY AND CHEMICAL REACTIONS

Topic: Chemical Equations and Stoichiometry

1. Introduction

Chemistry is sometimes called the central science because it connects physics, biology, and medicine. To understand how chemicals interact in the body or in a laboratory, we must first understand chemical reactions and how to measure the quantities involved — this is the essence of stoichiometry.

In simple terms, stoichiometry is the “accounting system” of chemistry — it ensures that we know how much reactant produces how much product.

2. Chemical Reactions

A chemical reaction occurs when one or more substances (reactants) are converted into new substances (products).

- Example:

2H2 + O2 → 2H2O

Reactants (starting materials) Products ( materials formed)

Here, hydrogen gas reacts with oxygen gas to form water.

Medical Relevance:

Think of a chemical reaction like a metabolic reaction in the human body.

For instance, when glucose reacts with oxygen in cellular respiration,

it produces carbon dioxide, water, and energy (ATP):

C6H12O6 + 6O2 → 6CO2 + 6H2O + Energy(ATP)

This reaction keeps our cells alive — a perfect example of chemistry in medicine.

3. Writing Chemical Equations

A chemical equation is a symbolic representation of a chemical change or process.

It is a way to represent the chemical reaction. It shows us:

• The chemical symbols of reactants and products

• The physical states of reactants and products– (s), (l), (g), (aq)

• Balanced equation (same number of atoms on each side)

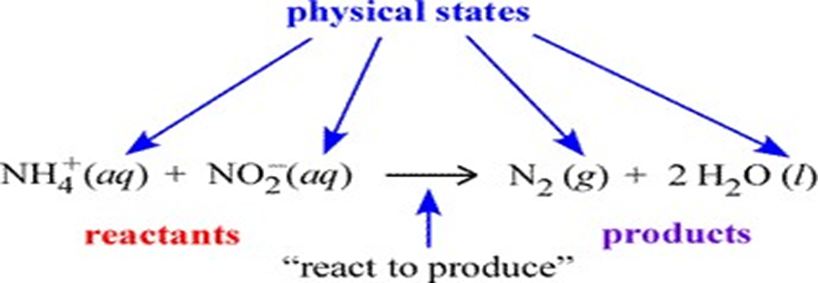

In the figure below, an example of chemical equation is labelled according to its components. The set of species on the left side of the rightward arrow are called the reactants; those on the right side are the products. The italicized abbreviations in parentheses indicate the physical state of each species. The common phases of matter are designated (s), (l), (g) for solid, liquid, and gas, respectively.

The (aq) seen at left designates a species dissolved in water to form what is called an aqueous solution. How we can translate, or read out, a chemical equation? Here, we could read the example equation as "an ammonium ion and a nitrite ion (in aqueous solution) react to produce one molecule of gaseous diatomic nitrogen and two molecules of water".

A chemical equation shows the relationship between reactants and products.

Parts of a chemical equation:

- Reactants – substances that react.

- Products – substances formed.

- Arrow (→) – means "yields" or "produces".

- Coefficients – numbers in front of chemical formulas that balance the equation.

Example:

N2 +3H2 →2NH3

This equation shows that one molecule of nitrogen reacts with three molecules of hydrogen to form two molecules of ammonia.

The number of atoms of each element must be the same on both sides of the equation. Chemical equation is a symbolic language in chemistry that you ought to practice using at every opportunity. Understanding and using chemical equations will help you feel more at home in the world of chemistry. Many problems in chemistry are most clearly analyzed by writing the applicable chemical equations, and failure to do so often results in being led astray.

Balancing chemical equations is a skill best learned by practice. A redeeming feature of this type of problem is that carefully checking that your equation satisfies a simple criterion, you know whether or not you have the right answer. We refer to an unbalanced chemical equation as a skeletal equation. The skeletal equation is only a qualitative expression - it tells us what the reactants and products of a reaction are. It does not provide us with the quantitative, or stoichiometric relationship of the reactants and products. A balanced chemical equation satisfies the criterion that the number of atoms of each type of element is the same on both sides of the equation. That this must be true for a properly balanced chemical equation is a result of the law of conservation of mass.

Many chemical equations in their skeletal form can be easily balanced by inspection because of their relative simplicity. However, for more complex equations, a more systematic approach is advisable.

1. The first principle of such an approach is to balance each atom type individually, and look at the equation to see how many formulas each atom type occurs in. One should start by balancing the atom type(s) that occur in the fewest number of formulas, and leave the atom type that occurs in the greatest number of formulas for last.

2. Another principle to recognize groupings of atoms in the formulas - such as polyatomic ions - that remain unchanged in the reaction, and treat them the same as if they were atoms.

3. Balance metals first, nonmetals second, and hydrogen and oxygen last.

4. If an element appears in more than one reactant or product, balance it after the others.

5. Use fractional coefficients if necessary, then multiply all coefficients by the denominator to get whole numbers.

Examples of balancing chemical equations

Example 1: Balance the following skeletal chemical equation:

ClO2 + H2O → HClO3 + HCl

Solution: To balance any equation, we need to keep track of the number of atoms on each side, trying to use coefficients for the atoms and molecules involved so the numbers of each atom type are the same on both sides. This is an iterative bookkeeping process, and sometimes it may seem that we just have to try things until something works. First off, let's see where we stand with the reaction as it is written:

atom reactants products ClO2 + H2O → HClO3 + HCl

Cl 1 2

H 2 2

O 3 3

Things look bright - there are three types of atoms to balance, and two of them are already balanced. But Cl is not balanced, and there is only one choice at this point: We must multiply the ClO2 species on the reactant side by 2 to bring the Cl atoms into balance. But this changes the

number of O atoms. So, we have:

atom reactants products 2 ClO2 + H2O → HClO3 + HCl

Cl 2 2

H 2 2

O 5 3

Now H and Cl are both balanced, but we have a problem with O. But note that if we multiply the O-containing species on the reactant side by 3, and the O-containing species on the product side by 5, we should get the same number of O atoms on each side. We keep our fingers crossed in hopes that this doesn't throw anything else out of balance:

atom reactants products 6 ClO2 + 3 H2O → 5 HClO3 + HCl

Cl 6 6

H 6 6

O 15 15

Great! our equation is balanced. It must always be possible to balance an equation representing any legitimate chemical reaction.

Example 2

C2H6 + O2

CO2+H2O

|

C |

|

|

|

Reactants |

Products |

|

2 C |

1 C |

|

6 H |

2 H |

|

2 O |

3 O |

C2H6 + 7/2O2 2CO2 + 3H2O

|

Reactants |

Products |

|

2 C |

2C |

|

6 H |

6 H |

|

7 O |

7O |

OR

2C2H6 + 7O2 4CO2 + 6H2O

|

Reactants |

Products |

|

4 C |

4 C |

|

12 H |

12 H |

|

14 O |

14 O |

Example 3:

1. Write the Unbalanced Equation: Fe+O2→Fe2O3

2. Count Atoms of Each Element:

• Reactants: Fe = 1, O = 2

• Products: Fe = 2, O = 3

3. Balance One Element at a Time:

• Start with oxygen. To balance the oxygens, find the least common multiple of 2 and 3, which is 6.

• Place coefficients to balance oxygen: 4Fe+3O2→2Fe2O3

4. Balance Iron Atoms:

• Reactants: Fe = 4 (from 4Fe)

• Products: Fe = 4 (from 2Fe₂O₃)

• Now the equation is balanced: 4Fe+3O2→2Fe2O3

RACK YOUR BRAIN

BALANCE THE FOLLOWING EQUATIONS:

1.

Mg +02 MgO

2. O3 O2

3. H2O2

H2O +O2

4. N2 + H2 NH3

5. Zn +AgCl ZnCl2 + Ag

6. S8 + O2

SO2

7. C3H8+O2→CO2+H2O

8. H2X +KOH→K2X +2H2O

9. Na +H2O → NaOH +H2

IN summary; Balancing Chemical Equations Entails:

Balancing ensures that the number of atoms of each element is the same on both sides of the equation.

Steps to balance equations:

- Write the unbalanced equation.

- Count the atoms of each element on both sides.

- Adjust coefficients to balance each element.

- Recheck to ensure atoms are equal on both sides.

- Never change subscripts (it changes the substance).

Example:

Unbalanced:

Fe+O2→Fe2O3

Balanced:

4Fe + 3O2 →2Fe2O3

6. Stoichiometric Calculations

Once an equation is balanced, you can use it to calculate quantities of reactants and products.

Key Concepts:

- Mole (mol):

The standard unit for measuring

chemical quantity.

1 mole = 6.022×10236.022 × 1023 particles (Avogadro’s number).

Molar Mass

The mass of one mole of a substance (g/mol).

- Example: H2O=

2(1.008)+16.00

=18.016 g/mol

Mole Ratio

The ratio of moles between substances from a balanced equation.

Example Calculation:

2H2 + O2 → 2H2O

If 4 moles of Hydrogen react completely, how many moles of water

will be formed fo?

From the equation, 2 moles of H2H_2H2 produce 2 moles of H2OH_2OH2O.

Thus, 4 moles of H2H_2H2 produce 4 moles of H2OH_2OH2O.

Limiting and Excess Reagents

In many reactions, one reactant runs out first — that’s the limiting reagent. The other, left over, is the excess reagent.

Example:

2H2 + O2 → 2H2O

Supposing; If you have 3 moles of Hydrogen and 2 moles of Oxygen:

From the Equation of reaction above,

- 2 moles of Hydrogen need 1 mole of Oxygen.

- So, For

3 moles Hydrogen, you need 1.5 moles Oxygen.

Since you have 2 moles O2, oxygen is in excess, and hydrogen is limiting.

Medical Relevance:

Think of oxygen and glucose in respiration — if oxygen is limited (as in

hypoxia), energy (ATP) production drops, even if glucose is abundant.

10. Importance of Stoichiometry in Medicine

- Drug dosage calculations — ensuring the right molar amount reaches target tissues.

- Respiratory physiology — balancing oxygen intake with carbon dioxide release.

- Biochemical analysis — determining concentrations in blood and urine.

- Pharmaceutical synthesis — exact mole ratios ensure correct drug purity and yield.

Summary Table

|

Concept |

Description |

Medical Analogy |

|

Chemical Reaction |

Reactants → Products |

Glucose + O₂ → CO₂ + H₂O |

|

Law of Conservation |

Mass is constant |

Matter is recycled in metabolism |

|

Stoichiometry |

Quantitative relation of reactants/products |

Drug dosage precision |

|

Limiting Reagent |

Substance used up first |

Oxygen shortage in hypoxia |

|

Combustion Reaction |

Burning with oxygen |

Cellular respiration |