INTRODUCTION TO CHEMISTRY AND ATOMIC THEORY

WEEK 1

TOPIC: INTRODUCTION TO CHEMISTRY AND ATOMIC THEORY

1. Introduction to Chemistry

Definition

Chemistry is the branch of science that studies the composition, structure, properties, and changes of matter.

Matter is anything that has mass and occupies space — air, blood, water, bones, etc.

Everyday Example:

1. Chemistry is like cooking:

- Ingredients (chemicals) are mixed in specific ratios.

- The heat (energy) causes them to transform into something new — just like a chemical reaction!

2. In the human body, chemistry is the language of life.

- The digestion of food, metabolism of drugs, respiration, and nerve transmission are all chemical processes.

- For instance, the conversion of glucose to energy (ATP) in cells follows the same principles as chemical reactions studied in chemistry.

Branches of chemistry:

General/Analytical chemistry (composition/properties/reaction)

Inorganic chemistry (compounds that do not contain Carbon)

Organic chemistry (compounds containing Carbon)

Physical chemistry (physical nature of matter)

Chemistry and other disciplines

Chemistry cuts across many disciplines of study such as:

Geology (geochemistry- soil, ores, minerals)

Biology (biochemistry- chemistry of proteins)

Agriculture (phytochemistry (antioxidants, proximate analysis)

Pharmacy

(pharmaceutical chemistry, pharmacokinetics) etc

2. Importance of Chemistry in Health and Medicine

- Pharmacology: Understanding how drugs react in the body (drug metabolism, absorption, and excretion).

- Biochemistry: Explains how enzymes, hormones, and DNA function chemically.

- Pathology: Chemical tests help diagnose diseases (e.g., blood glucose, cholesterol levels).

- Anesthesia and Radiology: Depend on chemical principles of gases and reactions.

- Sterilization: Use of chemical disinfectants (like ethanol and chlorine).

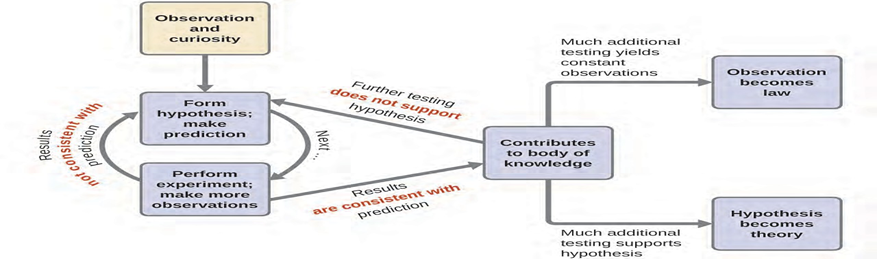

What are Scientific Methods? - a set of general principles that describes how any investigation is done. The method follows a specific sequence as indicated below:

6. Observation – describes and measures a data

7. Hypothesis – possible interpretation of the data (must be stated in a way that it can be verified or tested (e.g. If I say that putting my wet clothes in a dryer, the clothes will be dry in 30 minutes. The statement can be tested or verified by anybody. A hypothesis is a tentative explanation of observations that acts as a guide for gathering and checking information.

8. Experiments- test that is done to verified the hypothesis. We test a hypothesis by experimentation, calculation, and/or comparison with the experiments of others and then refine it as needed.

9. Theory – If a hypothesis turns out to be capable of explaining a large body of experimental data, it can reach the status of a theory. Scientific theories are well-substantiated, comprehensive, testable explanations of particular aspects of nature. Theories are accepted because they provide satisfactory explanations, but they can be modified if new data become available. The path of discovery that leads from question and observation to law or hypothesis to theory consistent data from experiments that confirms the hypothesis. Then the hypothesis becomes a theory

10. Law- When a theory remains true over a very long period of time, with unquestionable accuracy, it becomes a law. A statement that describes a natural phenomenon that always holds true under the same conditions. Unlike theories (which explain “why”), laws describe “what happens.” ‘One of such laws is ‘the law of gravity’.

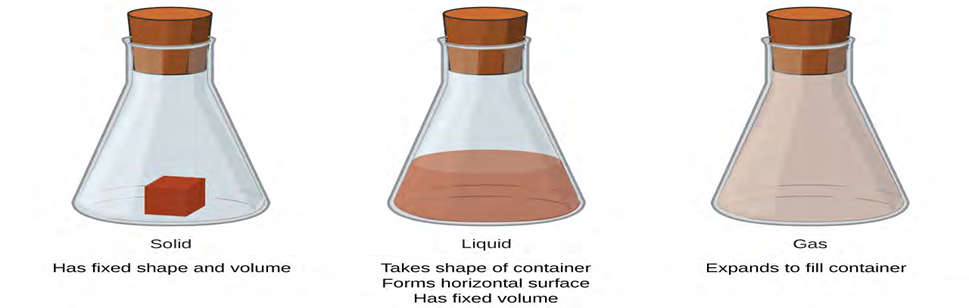

Phases and Classification of Matter

Matter is defined as anything that occupies space and has mass, and it is all around us. Solids and liquids are more obviously matter: We can see that they take up space, and their weight tells us that they have mass. Gases are also matter; if gases did not take up space, a balloon would

Solids, liquids, and gases are the three states of matter commonly found on earth. A solid is rigid and possesses a definite shape. A liquid flows and takes the shape of a container, except that it forms a flat or slightly curved upper surface when acted upon by gravity. (In zero gravity, liquids assume a spherical shape.) Both liquid and solid samples have volumes that are very nearly independent of pressure. A gas takes both the shape and volume of its container.

The three most common states or phases of matter are solid, liquid, and gas.

A fourth state of matter, plasma, occurs naturally in the interiors of stars. A plasma is a gaseous state of matter that contains appreciable numbers of electrically charged particles. The presence of these charged particles imparts unique properties to plasmas that justify their classification as a state of matter distinct from gases. In addition to stars, plasmas are found in some other high-temperature environments (both natural and man-made), such as lightning strikes, certain television screens, and specialized analytical instruments used to detect trace amounts of metals.

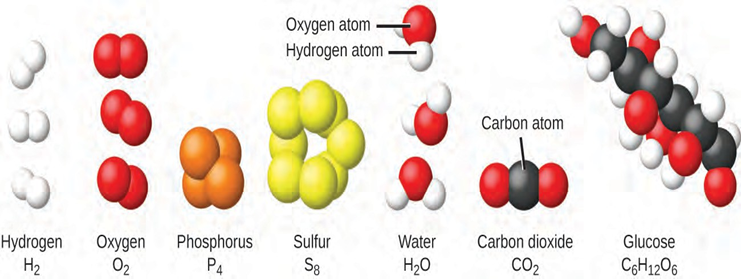

Atoms and Molecules

An atom is the smallest particle of an element that has the properties of that element and can enter into a chemical combination. Consider the element gold, for example. Imagine cutting a gold nugget in half, then cutting one of the halves in half, and repeating this process until a piece of gold remained that was so small that it could not be cut in half (regardless of how tiny your knife may be).

This minimally sized piece of gold is an atom (from the Greek atomos, meaning “indivisible”) This atom would no longer be gold if it were divided any further.

An atom is so small that its size is difficult to imagine. One of the smallest things we can see with our unaided eye is a single thread of a spider web:

These strands are about 1/10,000 of a centimeter (0.00001 cm) in diameter. Although the cross-section of one strand is almost impossible to see without a microscope, it is huge on an atomic scale. A single carbon atom in the web has a diameter of about 0.000000015 centimeter, and it would take about 7000 carbon atoms to span the diameter of the strand. To put this in perspective, if a carbon atom were the size of a dime, the cross-section of one strand would be larger than a football field, which would require about 150 million carbon atom “dimes” to cover it.

The elements hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur form molecules consisting of two or more atoms of the same element. The compounds water, carbon dioxide, and glucose consist of combinations of atoms of different elements

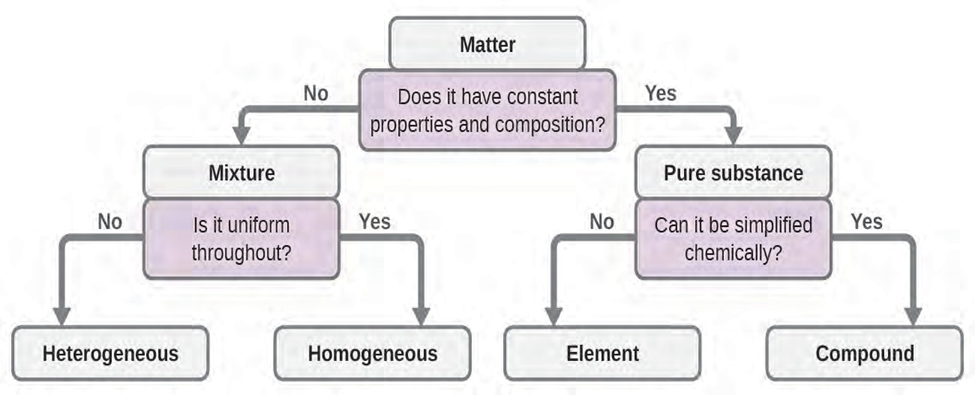

Classifying Matter

We can classify matter into several categories. Two broad categories are mixtures and pure substances.

A pure substance has a constant composition. All specimens of a pure substance have exactly the same makeup and properties. Any sample of sucrose (table sugar) consists of 42.1% carbon, 6.5% hydrogen, and 51.4% oxygen by mass. Any sample of sucrose also has the same physical properties, such as melting point, color, and sweetness, regardless of the source from which it is isolated.

Why This Matters in Medicine & Health

1. Drugs as Pure Substances

o Medications contain active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) that must be chemically pure.

o Example: Pure paracetamol (acetaminophen) has the same pain-relieving effect, regardless of the manufacturer.

2. Diagnostic Tests

o Pure reagents (like glucose solutions for blood sugar testing) are needed to ensure accurate results.

3. Nutrition

o Glucose and sucrose are pure substances with fixed energy values (4 kcal/g), which helps in diet planning and energy balance studies.

4. Toxicology

o Impurities in what should be a pure drug can cause adverse health effects (e.g., contaminated cough syrups with toxic compounds).

Medical Example

· If a nurse dissolves pure sodium chloride (NaCl) in water, the resulting solution is safe as IV saline (0.9%).

· But if the salt contains impurities (like heavy metals), it could be toxic to patients.

We can divide pure substances into two classes: elements and compounds.

Elements: are pure substances that cannot be broken down into simpler substances by chemical changes. Examples Iron, silver, gold, aluminum, sulfur, oxygen, and copper are familiar examples.

Compounds: are pure substances that can be broken down by chemical changes. This breakdown may produce either elements or other compounds, or both. Mercury(II) oxide, an orange, crystalline solid, can be broken down by heat into the elements mercury and oxygen. When heated in the absence of air, the compound sucrose is broken down into the element carbon and the compound water

(The initial stage of this process, when the sugar is turning brown, is known as caramelization—this is what imparts the characteristic sweet and nutty flavor to caramel apples, caramelized onions, and caramel). Silver(I) chloride is a white solid that can be broken down into its elements, silver and chlorine, by absorption of light. This property is the basis for the use of this compound in photographic films and photochromic eyeglasses (those with lenses that darken when exposed to light).

The properties of combined elements are different from those in the free, or uncombined, state. For example, white crystalline sugar (sucrose) is a compound resulting from the chemical combination of the element carbon, which is a black solid in one of its uncombined forms, and the two elements hydrogen and oxygen, which are colorless gases when uncombined. Free sodium, an element that is a soft, shiny, metallic solid, and free chlorine, an element that is a yellow-green gas, combine to form sodium chloride (table salt), a compound that is a white, crystalline solid.

Mixture

A mixture is composed of two or more types of matter that can be present in varying amounts and can be separated by physical changes, such as evaporation. There are two types of mixtures;

A mixture with a composition that varies from point to point is called a heterogeneous mixture. Examples of heterogeneous mixtures are chocolate chip cookies, muddy water and granite.

Medical Example: Whole blood is a heterogeneous mixture—you can separate plasma, white cells, and red cells by centrifugation.

A homogeneous mixture, also called a solution, exhibits a uniform composition and appears visually the same throughout. An example of a solution is a soft drinks, consisting of water, sugar, coloring, flavoring, and electrolytes mixed together uniformly. Each drop of a soft drink tastes the same because each drop contains the same amounts of water, sugar, and other components. Other examples of homogeneous mixtures include air, maple syrup, gasoline, and a solution of salt in water.

Medical Example:

· IV saline solution (0.9% NaCl) is homogeneous—every drop has the same concentration of salt.

· Blood plasma is a homogeneous mixture of water, proteins, electrolytes, and nutrients.

Why This Matters in Medicine & Health

· IV Therapy → Patients need homogeneous solutions (saline, glucose solutions) so each drop delivers the same dose.

· Diagnostics → Blood and urine are mixtures; lab tests often separate or analyze their components.

· Pharmacology → Syrups, injections, and inhalers are often mixtures (solutions or suspensions). Correct preparation ensures uniformity.

· Nutrition → Foods can be homogeneous (milk after processing) or heterogeneous (salads, cereals), which affects digestion and absorption.

Quick Comparison: Pure Substances vs. Mixtures

|

Feature |

.Pure Substance |

Mixture |

|

Composition |

Fixed |

Variable |

|

Properties |

Constant |

Depend on ratio of components |

|

Separation |

Chemical methods needed |

Physical methods (e.g., filtration, distillation) |

|

Examples |

Water (H₂O), glucose, oxygen |

Air, blood, saltwater, IV fluids |

A summary of how to distinquish between the various major classifications of matter is shown below:

Elemental Composition of Earth

|

Element |

Symbol |

Percent Mass |

|

Element |

Symbol |

Percent Mass |

|

oxygen |

O |

49.20 |

|

chlorine |

Cl |

0.19 |

|

silicon |

Si |

25.67 |

phosphorus |

P |

0.11 |

|

aluminum |

Al |

7.50 |

|

manganese |

Mn |

0.09 |

|

iron |

Fe |

4.71 |

carbon |

C |

0.08 |

|

|

calcium |

Ca |

3.39 |

sulfur |

S |

0.06 |

|

|

sodium |

Na |

2.63 |

barium |

Ba |

0.04 |

|

|

potassium |

K |

2.40 |

nitrogen |

N |

0.03 |

|

|

magnesium |

Mg |

1.93 |

fluorine |

F |

0.03 |

|

|

hydrogen |

H |

0.87 |

strontium |

Sr |

0.02 |

|

|

titanium |

Ti |

0.58 |

all others |

- |

0.47 |

Physical and Chemical Properties

Physical property/Physical Change: The characteristics that enable us to distinguish one substance from another are called properties. A physical property is a characteristic of matter that is not associated with a change in its chemical composition. Familiar examples of physical properties include density, color, hardness, melting and boiling points, and electrical conductivity. We can observe some physical properties, such as density and color, without changing the physical state of the matter observed. Other physical properties, such as the melting temperature of iron or the freezing temperature of water, can only be observed as matter undergoes a physical change. A physical change is a change in the state or properties of matter without any accompanying change in its chemical composition (the identities of the substances contained in the matter). Examples:

Wax melting (still wax, just liquid);

Ice melting into water (still H2O);

Sugar dissolving in coffee (no new substance formed);

Grinding a tablet into powder for easy swallowing;

Steam condensing into liquid water.

Other examples of physical changes include magnetizing and demagnetizing metals (as is done with common antitheft security tags) and grinding solids into powders (which can sometimes yield noticeable changes in color). In each of these examples, there is a change in the physical state, form, or properties of the substance, but no change in its chemical composition.

Medical Relevance:

Sterilization by boiling/evaporation → changes physical state of water but not its composition.

Nebulizers → convert liquid medicine into vapor without changing its chemical identity.

Drug formulation → crushing or dissolving a drug changes its form, not its chemical composition.

Chemical Property/ Chemical Change: The change of one type of matter into another type (or the inability to change) is a chemical property. Examples of chemical properties include Examples:

Flammability (ethanol burns in air to form CO₂ + H₂O).

Reactivity with acids/bases.

Oxidation (iron rusting).

· chromium does not oxidize. Nitroglycerin is very dangerous because it explodes easily; neon poses almost no hazard because it is very unreactive. To identify a chemical property, we look for a chemical change. A chemical change always produces one or more types of matter that differ from the matter present before the change. Examples:

Rusting of iron (iron → iron oxide).

Burning of wood (produces ash, CO₂, and H₂O).

Milk souring (lactic acid formed by bacteria).

Digestion of food (enzymes break down starch → glucose).

Metabolism of drugs in the liver.

The formation of rust is a chemical change because rust is a different kind of matter than the iron, oxygen, and water present before the rust formed. The explosion of nitroglycerin is a chemical change because the gases produced are very different kinds of matter from the original substance. Other examples of chemical changes include reactions that are performed in a lab (such as copper reacting with nitric acid), all forms of combustion (burning), and food being cooked, digested, or rotting.

|

Property/Change |

Definition |

Examples |

Medical Relevance |

|

Physical Property |

Can be observed without changing substance’s identity |

Color, density, boiling point |

Blood color, saline conductivity |

|

Physical Change |

Change in state/form without new substance |

Melting ice, dissolving sugar |

Crushing tablets, nebulization |

|

Chemical Property |

How a substance reacts chemically |

Flammability, acidity |

Drug reactivity, enzyme activity |

|

Chemical Change |

New substance formed |

Burning wood, souring milk |

Digestion, drug metabolism, sterilization |

Extensive and Intensive Properties of Matter

Properties of matter fall into one of two categories. If the property depends on the amount of matter present, it is an extensive property. The mass and volume of a substance are examples of extensive properties; for instance, a gallon of milk has a larger mass and volume than a cup of milk. The value of an extensive property is directly proportional to the amount of matter in question. Extensive Properties

· Depend on the amount of matter in the sample.

· Examples:

o Mass → A bag of IV saline weighs more than a single IV ampoule.

o Volume → 1 liter of blood plasma vs. 5 mL of plasma.

o Heat content (energy) → A large pot of hot soup contains more total heat than a single spoonful at the same temperature.

· Key Point: The value changes if the sample size changes.

Medical Relevance:

· The volume of blood loss is an extensive property—losing 1 liter of blood is life-threatening, while losing a few milliliters is usually harmless.

· The dose of a drug is an extensive property—the amount administered matters (e.g., 500 mg vs. 1 g of paracetamol).

If the property of a sample of matter does not depend on the amount of matter present, it is an intensive property. Temperature is an example of an intensive property. If the gallon and cup of milk are each at 20 °C (room temperature), when they are combined, the temperature remains at 20 °C. As another example, consider the distinct but related properties of heat and temperature. A drop of hot cooking oil spattered on your arm causes brief, minor discomfort, whereas a pot of hot oil yields severe burns. Both the drop and the pot of oil are at the same temperature (an intensive property), but the pot clearly contains much more heat (extensive property).

Medical & Health Applications

· Temperature vs. Fever

o Temperature (intensive): A patient’s body temperature of 39 °C is fever, whether the person weighs 40 kg or 100 kg.

o Heat content (extensive): Larger bodies store more heat energy at the same temperature, which is why obese patients may retain heat differently.

· Drug Concentration vs. Dose

o Concentration in blood (intensive): 10 mg/L of a drug is the same concentration regardless of total blood volume.

o Dose (extensive): 500 mg vs. 1000 mg paracetamol → the effect depends on the total amount given.

· Blood Volume vs. Blood Pressure

o Blood volume (extensive): 1 L vs. 5 L is not the same.

o Blood pressure (intensive): 120/80 mmHg describes the state of pressure regardless of how much blood is in circulation.

SUMMARY:

· Intensive = Quality (doesn’t change with size).

· Extensive = Quantity (depends on how much you have).

6. Chemical Reactions

Definition

A chemical reaction is a process where one or more substances (reactants) are transformed into new substances (products).

Example:

2H2 + O2 →2H2O

Examples:

1. Cooking an egg — once it’s cooked, it

cannot turn back into raw egg.

That’s a chemical change (irreversible reaction).

2.Cellular Respiration:

C6H12 O6 +6O2→ 6CO2 + 6H2O + Energy(ATP)

— how your body converts glucose into usable energy.

- Drug

Metabolism (in the liver):

Paracetamol is chemically broken down by enzymes into harmless metabolites. - Photosynthesis

(in plants):

Provides the oxygen we breathe and food we eat. - Acid–Base

Reactions:

Maintaining blood pH (7.35–7.45) depends on chemical buffers like bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) reacting with acids and bases.

7. Types of Chemical Reactions

|

Type |

Description |

Example |

Medical / Everyday Analogy |

|

Combination |

Two or more substances combine to form one |

2H₂ + O₂ → 2H₂O |

Formation of water in the body during metabolism |

|

Decomposition |

A compound breaks down into simpler substances |

2H₂O → 2H₂ + O₂ |

Breakdown of glucose in cellular respiration |

|

Single Displacement |

One element replaces another in a compound |

Zn + H₂SO₄ → ZnSO₄ + H₂ |

Displacement in drug–metal interactions |

|

Double Displacement |

Exchange of ions between two compounds |

NaCl + AgNO₃ → NaNO₃ + AgCl |

Precipitation in diagnostic tests (e.g. AgCl in chloride test) |

|

Combustion |

Reaction with oxygen releasing energy |

CH₄ + 2O₂ → CO₂ + 2H₂O |

Burning of glucose in cells for energy |

|

Neutralization |

Acid + Base → Salt + Water |

HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H₂O |

Antacids neutralizing excess stomach acid |

8. Summary

- Chemistry explains how matter behaves and how changes occur.

- Atoms are building blocks of matter.

- Molecules form when atoms combine.

- Chemical reactions drive life processes — digestion, respiration, drug metabolism, and detoxification.

- Understanding atomic theory helps in radiology, pharmacology, toxicology, and biochemistry.

ATOMIC THEORY (Historical Background)

a) Dalton’s Atomic Theory (1808)

- Matter is made up of indivisible particles called atoms.

- Atoms of the same element are identical; different elements have different atoms.

- Atoms combine in simple whole-number ratios to form compounds.

- Chemical reactions involve rearrangement of atoms — atoms are not created or destroyed.

Limitation: It couldn’t explain isotopes or subatomic particles.

b) Thomson’s Model (1898 – Plum Pudding Model)

- Atom is a positively charged sphere with negatively charged

electrons embedded within it.

Analogy: Like raisins in a pudding or chocolate chips in a cookie.

c) Rutherford’s Nuclear Model (1911)

- Most of the atom’s mass is concentrated in a small, dense nucleus.

- Electrons move around the nucleus in mostly empty space.

Experiment: Gold foil

experiment.

d) Bohr’s Model (1913)

- Electrons orbit the nucleus in specific energy levels (shells).

- Energy is absorbed or emitted when electrons jump between shells.

e) Quantum Mechanical Model

- Modern view: Electrons exist in regions called orbitals, not fixed paths.

- Predicts probabilities of finding an electron around the nucleus.

Modern Electronic Theory of Atoms

1. Introduction

The modern electronic theory of atoms explains how electrons are arranged and behave within atoms using quantum mechanics.

Earlier models (like Dalton’s, Thomson’s, Rutherford’s, and Bohr’s) described the atom’s structure but could not explain complex electron behavior — especially why atoms emit light in certain colors or how chemical bonds form.

Quantum mechanics came to solve these mysteries.

2. Development of Modern Atomic Theory

a) Bohr’s Model (1913)

- Proposed that electrons move around the nucleus in fixed energy levels (shells).

- Energy is absorbed or released when electrons jump between these levels.

Equation:

E=hνE = h\nuE=hν

Where:

- E = energy

- h = Planck’s constant

- ν = frequency of radiation

Limitation:

Bohr’s model only explained hydrogen (one-electron atom) — not atoms

with multiple electrons.

b) Quantum Mechanical Model (Modern View)

Developed by Erwin Schrödinger, Werner

Heisenberg, and others.

It treats electrons not as particles moving in definite orbits but as waves

existing in regions of probability.

Key idea:

We cannot pinpoint where an electron is, but we can predict where it is most

likely to be found — this region is called an orbital.

3. Important Principles of Quantum Mechanics

1. Wave-Particle Duality (de Broglie)

- Electrons behave both as particles (with mass) and waves (with wavelength).

- Just like light, which behaves as both a wave and a particle.

Medical example:

In X-rays and MRI, radiation (like electrons or photons) behaves both as

particles and waves, allowing medical imaging.

2. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle

It is impossible to know both the exact position and momentum of an electron at the same time.

Medical example:

In nuclear medicine, particle–wave uncertainty helps explain radiation

spread during imaging — we can predict where particles might be, but not

with exact certainty.

3. Schrödinger’s Wave Equation

- Describes the behavior of an electron as a wave.

- The solution to this equation gives orbitals, regions in space where electrons are most likely to be found.

4. Quantum Numbers

Quantum numbers are four numbers that describe the position and energy of an electron in an atom — like a unique address for each electron.

|

Quantum Number |

Symbol |

Describes |

Possible Values |

Example |

|

Principal |

n |

Main energy level (shell) |

1, 2, 3, 4… |

n = 1 (K shell), n = 2 (L shell) |

|

Azimuthal / Angular Momentum |

l |

Sublevel or shape of orbital |

0 → (n–1) |

l = 0 (s), 1 (p), 2 (d), 3 (f) |

|

Magnetic |

mₗ |

Orientation of orbital |

–l → +l |

For l = 1, mₗ = –1, 0, +1 |

|

Spin |

mₛ |

Spin of electron |

+½ or –½ |

Two possible spins per orbital |

Think of a hospital system:

- n (principal number): The hospital building (energy level)

- l (sublevel): The department (ward or clinic)

- mₗ (orbital): The specific bed/room where a patient (electron) stays

- mₛ (spin): Whether the patient faces up or down (↑ or ↓)

Each electron has a unique “hospital address” inside the atom!

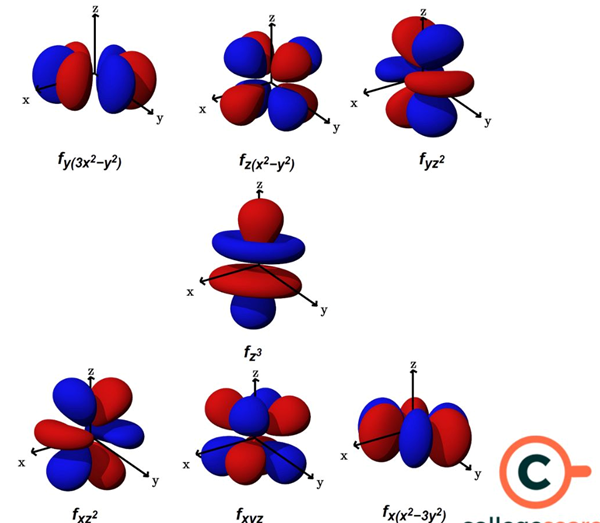

5. Shapes of Orbitals

|

Type |

Symbol |

Shape |

Maximum Electrons |

Analogy |

|

s-orbital |

s |

Spherical |

2 |

Like a round football field |

|

p-orbital |

p |

Dumbbell |

6 |

Like two balloons tied together |

|

d-orbital |

d |

Cloverleaf |

10 |

Complex, like flower petals |

|

f-orbital |

f |

Very complex |

14 |

Multilobed — rarely in basic atoms |

According to the quantum atomic model, an atom can have many possible numbers of orbitals. These orbitals can be categorized on the basis of their size, shape or orientation. A smaller sized orbital means there is a greater chance of getting an electron near the nucleus. The orbital wave function or ϕ is a mathematical function used for representing the coordinates of an electron. The square of the orbital wave function represents the probability of finding an electron.

This wave function also helps us in drawing boundary surface diagrams. Boundary surface diagrams of the constant probability density for different orbitals help us understand the shape of orbitals.

Let us represent the shapes of orbitals with the help of boundary

surface diagrams:

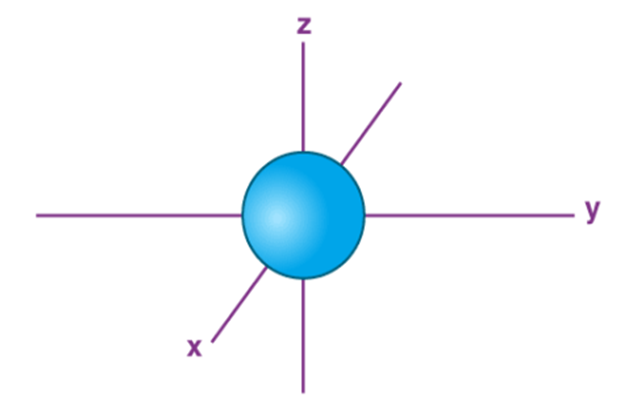

The Shape of s Orbitals

- The boundary surface diagram for the s orbital looks like a sphere having the nucleus as its centre which in two dimensions can be seen as a circle.

- Hence, we can say that s-orbitals are spherically symmetric having the probability of finding the electron at a given distance equal in all the directions.

- The size of the s orbital is also found to increase with the increase in the value of the principal quantum number (n), thus, 4s > 3s> 2s > 1s.

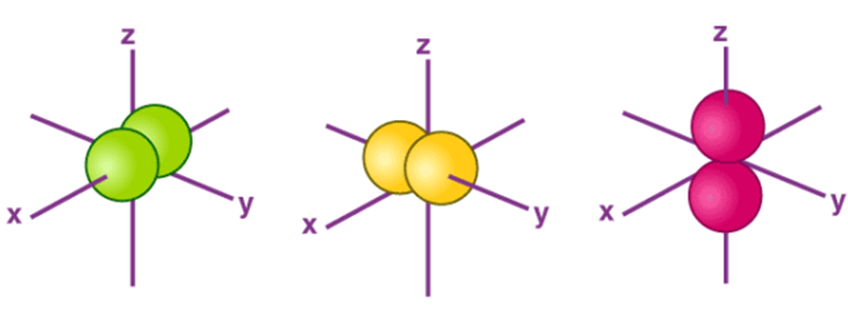

The Shape of p Orbitals

- Each p orbital consists of two sections better known as lobes which lie on either side of the plane passing through the nucleus.

- The three p orbitals differ in the way the lobes are oriented whereas they are identical in terms of size, shape, and energy.

- As the lobes lie along one of the x, y or z-axis, these three orbitals are given the designations 2px, 2py, and 2pz. Thus, we can say that there are three p orbitals whose axes are mutually perpendicular.

- Similar to s orbitals the size, and energy of p orbitals increase with an increase in the principal quantum number (4p > 3p > 2p).

The Shape of p Orbitals

- Each p orbital consists of two sections better known as lobes which lie on either side of the plane passing through the nucleus.

- The three p orbitals differ in the way the lobes are oriented whereas they are identical in terms of size, shape, and energy.

- As the lobes lie along one of the x, y or z-axis, these three orbitals are given the designations 2px, 2py, and 2pz. Thus, we can say that there are three p orbitals whose axes are mutually perpendicular.

- Similar to s orbitals the size, and energy of p orbitals increase with an increase in the principal quantum number (4p > 3p > 2p).

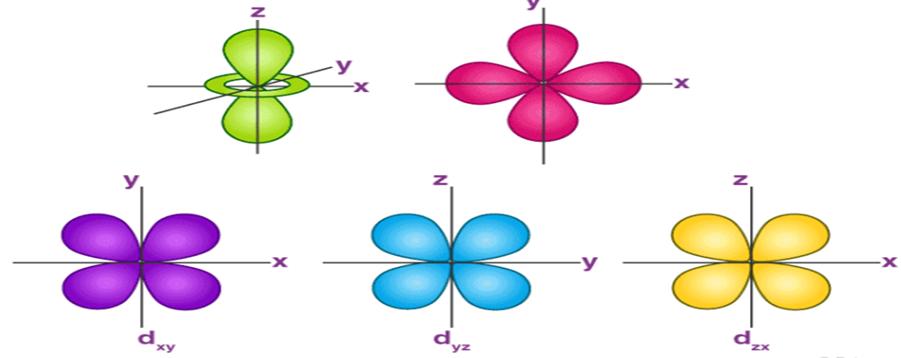

The Shape of d Orbitals

- The magnetic orbital quantum number for d orbitals is given as (-2,-1,0, 1,2). Hence, we can say that there are five d-orbitals.

- These orbitals are designated as dxy, dyz, dxz, dx2–y 2 and dz2.

- Out of these five d orbitals, the shapes of the first four d-orbitals are similar to each other, which is different from the dz2 orbital whereas the energy of all five d orbitals is the same.

6. Electronic Configuration

Definition

The arrangement of electrons in various orbitals of an atom.

Rules: Electrons are arranged in sub-orbital by three principles, viz:

Aufbau or building principles: electrons are filled into orbitals in order of increasing energy- 1s<2s<2p<3s<sp<4s<3d<4p<5s<4d<5p<6s<4f<5d etc

Pauli’s exclusion principle: Electrons spins on its axis and hence generates magnetic and electric fields. Electrons in the same degenerate orbital repels each other and therefore will have opposite spins number to be able to reside in the same orbital. Hence Pauli formulate the following rules: (i)The maximum number of electrons in a degenerate orbital is two (ii) the two electrons in a degenerate orbital have opposite quantum spin number (+/-). Each spin is represented by half headed arrows ( ). (iii) no two electron have all four principal quantum numbers the same

Hund’s rule (the principle of maximum multiplicity): degenerate orbitals are singly filled before pairing up. As a result, an atom tends to have as many unpaired electrons as possible, In order words, electrons avoid repelling each other by seeking out empty shells to fill up instead of pairing up.

The electronic arrangement can also be written in the format shown below by following the direction of the arrow

|

1s 2s |

|

2p |

|

3s |

|

3p |

|

3d |

|

4s |

|

4p |

|

4d |

|

4f |

|

5s |

|

5p |

|

5d |

|

5f |

|

6s |

|

6p |

|

6d |

|

6f |

Electronic Configuration and Electronic Diagram

The shorthand form of representing the arrangement of electrons in orbitals can be in form of a diagram or in a specified configuration.

For example, carbon has 6 valence electrons and can be represented thus:

Electronic Configuration: 1s2 2s22p2

The correct arrangement of the sub-orbitals is show in the previous slide

Electronic Diagram: The electronic diagram of carbon can be drawn as shown below

|

2s |

|

2p |

|

1s |

Abbreviated Format

Another way of writing electronic configuration is to use the Abbreviated format. This involves using the configuration of noble gas preceding the desired element and filling the remaining valence electrons in the next principal quantum level

For example, Sodium has 11 valence electrons: 1s2 2s22p63s1. The nearest noble gas before sodium is Neon with electronic configuration: 1s2 2s22p61s2 2s22p6 which is one electron shorn of sodium configuration. Hence sodium configuration can be written as: [Ne]3s1 which is the condensed format of sodium configuration.

Examples

- Hydrogen (Z = 1): 1s¹

- Helium (Z = 2): 1s²

- Carbon (Z = 6): 1s² 2s² 2p²

- Sodium (Z = 11): 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s¹

- Calcium (Z = 20): 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶ 4s²

7. Periodic Properties and Atomic Structure

The arrangement of electrons explains periodic trends:

|

Property |

Definition |

Trend |

Medical Analogy |

|

Atomic Radius |

Size of an atom |

Decreases across a period, increases down a group |

Small drug molecules penetrate cells more easily |

|

Ionization Energy |

Energy to remove an electron |

Increases across a period |

Similar to how tightly bound oxygen is to hemoglobin |

|

Electronegativity |

Tendency to attract electrons |

Increases across a period |

Like the “attraction” between receptor and ligand in drug binding |

|

Electron Affinity |

Energy change when atom gains an electron |

Increases across a period |

Like enzymes capturing substrates more efficiently |

Medical Relevance of Modern Atomic Theory

- Drug–Receptor Interaction:

Electron configuration determines how drugs bind to receptors — e.g., hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces depend on electron density. - Radiation and Imaging:

- X-rays and CT scans depend on the interaction of high-energy electrons with tissues.

- Understanding atomic structure helps explain ionizing radiation effects on cells.

- Isotopes in Medicine:

- Cobalt-60 and Iodine-131 used in radiotherapy and diagnosis are based on the concept of atomic nuclei and electron transitions.

- Enzyme Catalysis:

- The reaction rates in biochemistry depend on how electrons are shared or transferred between molecules (redox reactions).

Summary

- The modern atomic theory uses quantum mechanics to describe how electrons behave as waves and particles.

- Orbitals represent regions where electrons are likely to be found.

- Quantum numbers act like an address for each electron.

- Electron configuration determines the chemical behavior of elements.

- These concepts explain biochemical reactions, drug action, and radiation therapy in medicine.

10. Review Questions

- What are the key differences between Bohr’s and Schrödinger’s atomic models?

- Explain wave-particle duality and its medical relevance.

- List and describe the four quantum numbers.

- Write the electron configurations of Na, Cl, and Fe.

- State and explain the three rules governing electron filling.

- How does atomic structure explain the action of radioactive isotopes in medicine.

Electronic Configuration and the Periodic Table

1. Introduction

The Periodic Table is the chemist’s map of elements — it organizes all known elements according to their atomic structure and electronic configuration.

The arrangement helps us:

- Predict how elements behave in chemical reactions.

- Understand their valence electrons, bonding capacity, and biological roles.

In medicine and biochemistry, this knowledge helps explain:

- How ions like Na⁺, K⁺, and Ca²⁺ function in the body.

- How transition metals like Fe, Cu, and Zn act as cofactors in enzymes.

- How radioactive elements behave in diagnostic imaging and radiation therapy.

· Classification of Elements

· Many elements differ dramatically in their chemical and physical properties, but some elements are similar in their behaviors. We can sort the elements into large classes with common properties:

· Metals: Elements that are shiny, malleable, ductile, good conductors of heat and electricity.

· Nonmetals: Elements that appear dull, poor conductors of heat and electricity;

· Metalloids: Elements that conduct heat and electricity moderately well, and possess some properties of metals and some properties of nonmetals.

·

· The elements can also be classified based on their position in the periodic table

· The main-group elements (or representative elements) in the columns labeled 1, 2, and 13–18; The transition metals in the columns labeled 3–12; and

· Inner transition metals in the two rows at the bottom of the table (the top-row elements are called lanthanides and the bottom-row elements are actinides.

·

· The elements can be subdivided further by more specific properties, such as the composition of the compounds they form:

· Alkali metals:The elements in group 1 (the first column) form compounds that consist of one atom of the element and one atom of hydrogen. and they all have similar chemical properties.

· Alkaline earth metals: The elements in group 2 (the second column) form compounds consisting of one atom of the element and two atoms of hydrogen, with similar properties among members of that group.

· The pnictogens (group 15)

· The Halogens (group 17),

· The Noble gases (group 18 or zero, also known as inert or rare gases).

Electronic Configuration and the Periodic Table

a) Periodic Law

The properties of elements are periodic functions of their atomic numbers — that is, elements show repeating patterns when arranged by increasing atomic number.

b) Structure of the Periodic Table

The modern periodic table is arranged into:

- Periods (rows): 7 horizontal rows representing energy levels (n = 1–7)

- Groups (columns): 18 vertical columns showing elements with similar valence electron configurations

c) Blocks of the Periodic Table

The table is divided based on the type of orbital being filled:

|

Block |

Sublevel Being Filled |

Example Elements |

Range of Groups |

Example Configuration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s-block |

s orbital |

H, He, Li, Na, Mg |

1–2 |

ns¹–² |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

p-block |

p orbital |

C, N, O, F, Cl |

13–18 |

ns² np¹–⁶ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

d-block |

d orbital (Transition metals) |

Fe, Cu, Zn |

3–12 |

(n–1)d¹–¹⁰ ns⁰–² |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

f-block |

f orbital (Lanthanides/Actinides) |

Ce, U |

Inner transition |

(n–2)f¹–¹⁴ (n–1)d⁰–¹ ns² |

a) Groups (Columns)

Elements in the same group have:

- Same number of valence electrons

- Similar chemical and physical properties

|

Group |

Name |

Valence Electrons |

Example |

Medical Relevance |

|

1 |

Alkali metals |

1 |

Na, K |

Important for nerve impulses, fluid balance |

|

2 |

Alkaline earth metals |

2 |

Ca, Mg |

Bone formation, muscle contraction |

|

17 |

Halogens |

7 |

Cl, I |

Used as disinfectants and in thyroid hormones |

|

18 |

Noble gases |

8 |

He, Ne, Ar |

Inert gases, helium used in cryogenics and MRI cooling |

b) Periods (Rows)

- Each period represents a new energy level (shell) being filled.

- Properties change gradually across a period due to change in effective nuclear charge and valence electron configuration.

5. Periodic Trends and Their Significance

|

Property |

Trend Across a Period |

Trend Down a Group |

Medical/Everyday Examples |

|

Atomic Radius |

Decreases (nucleus pulls electrons closer) |

Increases (more shells added) |

Like tightening or loosening a belt — atoms “shrink” or “expand” |

|

Ionization Energy (Energy to remove one electron) |

Increases |

Decreases |

Like removing oxygen from hemoglobin — tightly bound in some, loosely in others |

|

Electronegativity (Attraction for electrons) |

Increases |

Decreases |

Like magnet strength — stronger across a period |

|

Electron Affinity |

Increases |

Decreases |

Similar to how receptors “attract” certain ligands more strongly |

|

Metallic Character |

Decreases |

Increases |

Explains why Na (metal) is reactive but Cl (nonmetal) forms salts |

Example of Periodic Behavior

- Sodium (Na): 1s²2s²2p⁶3s¹ → reactive metal, donates electrons easily.

- Chlorine (Cl): 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁵ → reactive nonmetal, gains electrons easily.

- Together, they form NaCl (table salt), essential for maintaining electrolyte balance in the body.

6. Special Groups and Their Biological Importance

|

Element/Group |

Function in the Body |

|

Na⁺ & K⁺ (Group 1) |

Maintain osmotic balance and nerve transmission |

|

Ca²⁺ & Mg²⁺ (Group 2) |

Bone and muscle function, enzyme activation |

|

Fe, Cu, Zn (Transition Metals) |

Components of hemoglobin, cytochromes, and enzymes |

|

I (Halogen) |

Part of thyroid hormones (T₃, T₄) regulating metabolism |

|

C, H, O, N (p-block) |

Basic building blocks of biomolecules (proteins, carbs, lipids) |

7. Relationship Between Electronic Configuration and Chemical Behavior

The valence electrons (outermost electrons) determine how atoms bond or react.

|

Example |

Configuration |

Behavior |

|

Na (Z=11): 1s²2s²2p⁶3s¹ |

Loses 1 electron → Na⁺ |

Metal (donor) |

|

Cl (Z=17): 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁵ |

Gains 1 electron → Cl⁻ |

Nonmetal (acceptor) |

|

O (Z=8): 1s²2s²2p⁴ |

Gains 2 electrons → O²⁻ |

Forms oxides, vital for energy release |

|

Ca (Z=20): [Ar]4s² |

Loses 2 electrons → Ca²⁺ |

Essential for muscle contraction |

8. Everyday and Medical Relevance

- Electrolyte Balance:

Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, and Cl⁻ ions maintain nerve impulses, heart rhythm, and fluid balance. - Oxygen Transport:

Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ ions in hemoglobin depend on transition metal chemistry. - Drug Design:

Electronic structure predicts how drugs interact with enzymes and receptors. - Radiotherapy:

Elements like Cobalt-60 (transition metal isotope) used for cancer treatment are chosen for their electronic and nuclear properties. - Biochemical Catalysis:

Zn²⁺ in carbonic anhydrase and Mg²⁺ in ATP reactions rely on electron configuration for proper catalytic function.

9. Step-by-Step Summary on the Periodic Table

1. Arrangement by Atomic Mass:

In the early stages of the periodic table's development, elements were arranged in order of increasing atomic mass. Chemists observed that certain properties of elements repeated periodically as their atomic masses increased.

2. Observation of Periodic Trends:

As elements were arranged by atomic mass, scientists started to notice patterns in their properties.

Certain properties, such as atomic radius, electronegativity, and ionization energy, showed periodic trends, meaning they varied in a regular and predictable manner across the elements.

3. Mendeleev's Periodic Law:

Dmitri Mendeleev, a Russian chemist, formulated the Periodic Law in 1869.

Mendeleev arranged the elements in order of increasing atomic mass and grouped them based on their similar chemical properties.

He left gaps for undiscovered elements and predicted their properties based on the periodic trends and the patterns he observed.

4. Discovery of Atomic Number:

In the early 20th century, Henry Moseley's experiments with X-ray spectroscopy revealed a fundamental property of elements called atomic number.

Atomic number represents the number of protons in an atom's nucleus and determines an element's identity.

Moseley's discovery led to the understanding that the periodic table should be arranged based on atomic number rather than atomic mass.

5. Modern Periodic Table:

The modern periodic table organizes elements based on their atomic number, with elements arranged in order of increasing atomic number from left to right and top to bottom.

Elements are grouped into periods (horizontal rows) and groups/families (vertical columns) based on their electron configurations and similar properties.

The periodic table consists of multiple blocks, including the s-block, p-block, d-block, and f-block, representing the different types of orbitals that electrons occupy.

6. Further Refinements and Expansions:

Over time, the periodic table has been refined and expanded as new elements have been discovered and synthesized.

![]() Elements beyond atomic number 118 are yet to be officially named and have temporary systematic names based on their

atomic numbers.

Elements beyond atomic number 118 are yet to be officially named and have temporary systematic names based on their

atomic numbers.

The Periodic Table is divided into Several Blocks

1. S-block: Elements in the first two groups (Group 1 and Group 2) are called s-block elements. They have their outermost electron(s) in the s orbital.

2. P-block: Elements in groups 13 to 18, excluding helium, are known as p-block elements. They have their outermost electron(s) in the p orbital.

3. D-block: Elements in groups 3 to 12 are called d-block elements or transition metals. They have their outermost electron(s) in the d orbital.

4. F-block: The elements at the bottom of the periodic table, also known as inner transition metals, are called f-block elements. They have their outermost electron(s) in the f orbital. The f-block is further divided into the lanthanide and actinide series.

The periodic table provides information about an element's atomic mass, atomic radius, electronegativity, and various other properties. It also helps predict an element's reactivity, bonding patterns, and potential chemical reactions.

10. Review Questions

- Define electronic configuration and state the three rules guiding electron filling.

- Differentiate between periods and groups in the periodic table.

- Write the electronic configurations for Na, Ca, and Cl, and explain their chemical behavior.

- Explain the relationship between valence electrons and periodic trends.

- How is the periodic table divided into s, p, d, and f blocks?

- Mention three ways electronic configuration is important in medicine.

- Why do noble gases show little or no reactivity?

- Explain the biological significance of Ca²⁺ and Fe²⁺ ions in the bod

: Measurements

What is Measurement? Measurement is the assigning of numerals to objects, events, etc. Measurements provide the macroscopic information that is the basis of most of the hypotheses, theories, and laws that describe the behavior of matter and energy in both the macroscopic and microscopic domains of chemistry. Every measurement provides three kinds of information: the size or magnitude of the measurement (a number); a standard of comparison for the measurement (a unit); and an indication of the uncertainty of the measurement. While the number and unit are explicitly represented when a quantity is written, the uncertainty is an aspect of the measurement result that is more implicitly represented.

The number in the measurement can be represented in different ways, including decimal form and scientific notation. (Scientific notation is also known as exponential notation;) For example, the maximum takeoff weight of a Boeing 777-200ER airliner is 298,000 kilograms, which can also be written as 2.98 × 105 kg. The mass of the average mosquito is about 0.0000025 kilograms, which can be written as 2.5 × 10−6 kg.

Without units, a number can be meaningless, confusing, or possibly life threatening. Suppose a doctor prescribes phenobarbital to control a patient’s seizures and states a dosage of “100” without specifying units. Not only will this be confusing to the medical professional giving the dose, but the consequences can be dire: 100 mg given three times per day can be effective as an anticonvulsant, but a single dose of 100 g is more than 10 times the lethal amount.

We usually report the results of scientific measurements in SI units. Other units can be derived from these base units. The standards for these units are fixed by international agreement, and they are called the International System of Units or SI Units (from the French, Le Système International d’Unités). SI units have been used by the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) since 1964.

Why Units Matter in Medicine

- Without units, numbers are meaningless and dangerous.

- Case Example:

- If a doctor prescribes “100” phenobarbital without specifying units:

- 100 mg/day → therapeutic dose.

- 100 g → lethal overdose (over 1,000× too much).

Lesson: Always record number + unit.

Medical Relevance of Accurate Measurements

- Dosage calculations – Overdose or underdose can harm patients.

- Diagnostics – Blood glucose, cholesterol, and blood pressure depend on precise measurements.

- IV therapy – Flow rates must be measured carefully (e.g., 50 mL/hr vs. 500 mL/hr makes the difference between safe hydration and fluid overload).

- Research & Clinical Trials – Drug effectiveness depends on reproducible measurements.

Base Units of the SI System

|

Property Measured |

Name of Unit |

Symbol of Unit |

|

length |

meter |

m |

|

mass |

kilogram |

kg |

|

time |

second |

s |

|

temperature |

kelvin |

K |

|

electric current |

ampere |

A |

|

amount of substance |

mole |

mol |

|

luminous intensity |

candela |

cd |

We also use fractions or multiples of units in the SI system, but these fractions or multiples are always powers of 10. Fractional or multiple SI units are named using a prefix and the name of the base unit. For example, a length of 1000 meters is also called a kilometer because the prefix kilo means “one thousand,” which in scientific notation is 103 (1 kilometer = 1000 m = 103 m). The prefixes used and the powers to which 10 are raised are listed in the table below:

|

Prefix |

Symbol |

Factor |

Example |

|

femto |

f |

10−15 |

1 femtosecond (fs) = 1 × 10−15 m (0.000000000000001 s) |

|

pico |

p |

10−12 |

1 picometer (pm) = 1 × 10−12 m (0.000000000001 m) |

|

nano |

n |

10−9 |

4 nanograms (ng) = 4 × 10−9 g (0.000000004 g) |

|

micro |

µ |

10−6 |

1 microliter (μL) = 1 × 10−6 L (0.000001 L) |

|

milli |

m |

10−3 |

2 millimoles (mmol) = 2 × 10−3 mol (0.002 mol) |

|

centi |

c |

10−2 |

7 centimeters (cm) = 7 × 10−2 m (0.07 m) |

|

deci |

d |

10−1 |

1 deciliter (dL) = 1 × 10−1 L (0.1 L) |

|

kilo |

k |

103 |

1 kilometer (km) = 1 × 103 m (1000 m) |

|

mega |

M |

106 |

3 megahertz (MHz) = 3 × 106 Hz (3,000,000 Hz) |

|

giga |

G |

109 |

gigayears (Gyr) = 8 × 109 yr (8,000,000,000 Gyr) |

|

tera |

T |

1012 |

5 terawatts (TW) = 5 × 1012 W (5,000,000,000,000 W) |

This section introduces four of the SI base units commonly used in chemistry.

Length

The standard unit of length in both the SI and original metric systems is the meter (m). A meter was originally specified as 1/10,000,000 of the distance from the North Pole to the equator. It is now defined as the distance light in a vacuum travels in 1/299,792,458 of a second. A meter is about 3 inches longer than a yard. One meter is about 39.37 inches or 1.094 yards. Longer distances are often reported in kilometers (1 km = 1000 m = 103 m), whereas shorter distances can be reported in centimeters (1 cm = 0.01 m = 10−2 m) or millimeters (1 mm = 0.001 m = 10−3 m).

Mass

The standard unit of mass in the SI system is the kilogram (kg). A kilogram was originally defined as the mass of a liter of water (a cube of water with an edge length of exactly 0.1 meter). It is now defined by a certain cylinder of platinum-iridium

alloy, which is kept in France. Any object with the same mass as this cylinder is said to have a mass of 1 kilogram. One kilogram is about 2.2 pounds. The gram (g) is exactly equal to 1/1000 of the mass of the kilogram (10−3 kg).

This replica prototype kilogram is housed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Maryland. (credit: National Institutes of Standards and Technology)

Temperature

Temperature is an intensive property. The SI unit of temperature is the kelvin (K). The IUPAC convention is to use kelvin (all lowercase) for the word, K (uppercase) for the unit symbol, and neither the word “degree” nor the degree symbol (°). The degree Celsius (°C) is also allowed in the SI system, with both the word “degree” and the degree symbol used for Celsius measurements. Celsius degrees are the same magnitude as those of kelvin, but the two scales place their zeros in different places. Water freezes at 273.15 K (0 °C) and boils at 373.15 K (100 °C) by definition, and normal human body temperature is approximately 310 K (37 °C).

Time

The SI base unit of time is the second (s). Small and large time intervals can be expressed with the appropriate prefixes; for example, 3 microseconds = 0.000003 s = 3 × 10−6 and 5 megaseconds = 5,000,000 s = 5 × 106 s. Alternatively, hours, days, and years can be used.

Derived SI Units

We can derive many units from the seven SI base units. For example, we can use the base unit of length to define a unit of volume, and the base units of mass and length to define a unit of density.

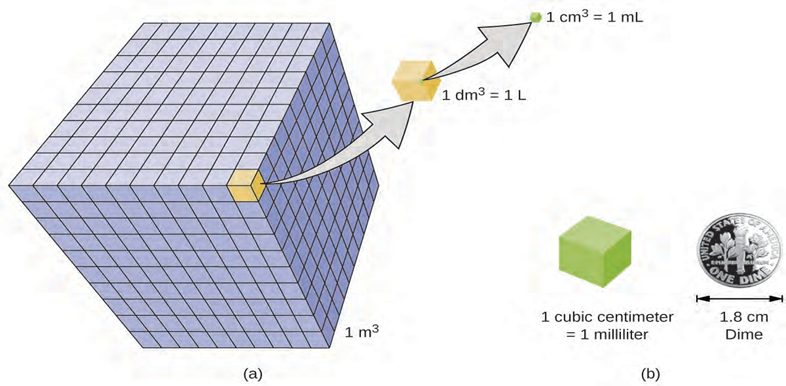

Volume

Volume is the measure of the amount of space occupied by an object. The standard SI unit of volume is defined by the base unit of length. The standard volume is a cubic meter (m3), a cube with an edge length of exactly one meter. To dispense a cubic meter of water, we could build a cubic box with edge lengths of exactly one meter. This box would hold a cubic meter of water or any other substance.

A more commonly used unit of volume is derived from the decimeter (0.1 m, or 10 cm). A cube with edge lengths of exactly one decimeter contains a volume of one cubic decimeter (dm3). A liter (L) is the more common name for the cubic decimeter. One liter is about 1.06 quarts.

A cubic centimeter (cm3) is the volume of a cube with an edge length of exactly one centimeter. The abbreviation cc (for cubic centimeter) is often used by health professionals. A cubic centimeter is also called a milliliter (mL) and is 1/1000 of a

The relative volumes are shown for cubes of 1 m3, 1 dm3 (1 L), and 1 cm3 (1 mL) (not to scale). (b) The diameter of a dime is compared relative to the edge length of a 1-cm3 (1-mL) cube.

Density

We use the mass and volume of a substance to determine its density. Thus, the units of density are defined by the base units of mass and length.

The density of a substance is the ratio of the mass of a sample of the substance to its volume. The SI unit for density is the kilogram per cubic meter (kg/m3). For many situations, however, this as an inconvenient unit, and we often use grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm3) for the densities of solids and liquids, and grams per liter (g/L) for gases. Although there are exceptions, most liquids and solids have densities that range from about 0.7 g/cm3 (the density of gasoline) to 19 g/cm3 (the density of gold). The density of air is about 1.2 g/L. The table below shows the densities of some common substances.

Densities of Common Substances

|

Solids |

Liquids |

Gases (at 25 °C and 1 atm) |

|

ice (at 0 °C) 0.92 g/cm3 |

water 1.0 g/cm3 |

dry air 1.20 g/L |

|

oak (wood) 0.60–0.90 g/cm3 |

ethanol 0.79 g/cm3 |

oxygen 1.31 g/L |

|

iron 7.9 g/cm3 |

acetone 0.79 g/cm3 |

nitrogen 1.14 g/L |

|

copper 9.0 g/cm3 |

glycerin 1.26 g/cm3 |

carbon dioxide 1.80 g/L |

|

lead 11.3 g/cm3 |

olive oil 0.92 g/cm3 |

helium 0.16 g/L |

|

silver 10.5 g/cm3 |

gasoline 0.70–0.77 g/cm3 |

neon 0.83 g/L |

|

gold 19.3 g/cm3 |

mercury 13.6 g/cm3 |

radon 9.1 g/L |

While there are many ways to determine the density of an object, perhaps the most straightforward method involves separately finding the mass and volume of the object, and then dividing the mass of the sample by its volume. In the following example, the mass is found directly by weighing, but the volume is found indirectly through length measurements.

|

|

Calculation of Density

What is the density of lead if a cube of lead has an edge length of 2.00 cm and a mass of 90.7 g?

The density of a substance can be calculated by dividing its mass by its volume. The volume of a cube is calculated by cubing the edge length.

volume of lead cube = 2.00 cm × 2.00 cm × 2.00 cm = 8.00 cm3

Density = mass/volume

= 90.7 g/8.00cm3

=11.3 g/cm3

Measurement Uncertainty, Accuracy, and Precision

Counting is the only type of measurement that is free from uncertainty, provided the number of objects being counted does not change while the counting process is underway. The result of such a counting measurement is an example of an exact number. If we count eggs in a carton, we know exactly how many eggs the carton contains. The numbers of defined quantities are also exact. By definition, 1 foot is exactly 12 inches, 1 inch is exactly 2.54 centimeters, and gram is exactly 0.001 kilogram. Quantities derived from measurements other than counting, however, are uncertain to varying extents due to practical limitations of the measurement process used.

Significant Figures in Measurement

The numbers of measured quantities, unlike defined or directly counted quantities, are not exact. To measure the volume of liquid in a graduated cylinder, you should make a reading at the bottom of the meniscus, the lowest point on the curved surface of the liquid.

Significant Figures in Calculations

A second important principle of uncertainty is that results calculated from a measurement are at least as uncertain as the measurement itself. We must take the uncertainty in our measurements into account to avoid misrepresenting the uncertainty in calculated results. One way to do this is to report the result of a calculation with the correct number of significant figures, which is determined by the following three rules for rounding numbers:

1. Any digit that is not zero is significant

1.234kg (4 significant figures)

2. Zeros to the left of the first nonzero digit are not significant

0.08L (1 significant figure)

3. If a number is greater than 1, then all zeros to the right of the decimal point are significant

2.0 mg (2 significant figures)

4. If a number is less than 1, then only the zeros that are at the end and in the middle of the number are significant

0.420 g (3 significant figures)

1. If the digit to be dropped (the one immediately to the right of the digit to be retained) is less than 5, we “round down” and leave the retained digit unchanged; if it is more than 5, we “round up” and increase the retained digit by 1; if the dropped digit is 5, we round up or down, whichever yields an even value for the retained digit. (The last part of this rule may strike you as a bit odd, but it’s based on reliable statistics and is aimed at avoiding any bias when dropping the digit “5,” since it is equally close to both possible values of the retained digit.)

Significant Figures: Addition & Subtraction

If addition or subtraction:

1. must have same power before addition or subtraction

2. sig. fig. in the answer is as the smaller digits after decimal point

4.31 ×104

+

3. 9×103 ( 0.39 ×104)

= 4.70 ×104(3 SF)

7.4 ×103

+ (1 decimal digit: this has the smallest digit)

0.10×103

= 7.5 ×103 (2 SF)

Significant Figures: Multiplication & Division

If multiplication or division:

1- add exponent for multiplication or subtract exponent for division

2- write the answer with the smaller sig. fig.

|

( 8.0 ×104) |

(5.00×102) = 40×106 |

or 4 .0×107 |

|

(2 SF) |

(3 SF) |

(2 SF) |

4.51 x 3.6666 = 16.53636 ≈ 16.5

(3 sf) (5 sf) (3 sf)

6.8 ÷ 112.04 = 0.0606926 ≈ 0.061

(2 sf) (5 sf) (2 sf)

The following examples illustrate the application of this rule in rounding a few different numbers to three significant figures:

a. 0.028675 rounds “up” to 0.0287 (the dropped digit, 7, is greater than 5)

b. 18.3384 rounds “down” to 18.3 (the dropped digit, 3, is lesser than 5)

c. 6.8752 rounds “up” to 6.88 (the dropped digit is 5, and the retained digit is even)

d. 92.85 rounds “down” to 92.8 (the dropped digit is 5, and the retained digit is even) Let’s work through these rules with a few examples.

Rounding Numbers

Round the following to the indicated number of significant figures:

(a) 31.57 (to two significant figures)

(b) 8.1649 (to three significant figures)

(c) 0.051065 (to four significant figures)

(d) 0.90275 (to four significant figures)

Solution

(a) 31.57 rounds “up” to 32 (the dropped digit is 5, and the retained digit is even)

(b) 8.1649 rounds “down” to 8.16 (the dropped digit, 4, is lesser than 5)

(c) 0.051065 rounds “down” to 0.05106 (the dropped digit is 5, and the retained digit is even)

(d) 0.90275 rounds “up” to 0.9028 (the dropped digit is 5, and the retained digit is even)

Rack Your Brain

Round the following to the indicated number of significant figures:

(a) 0.424 (to two significant figures)

(b) 0.0038661 (to three significant figures)

(c) 421.25 (to four significant figures)

(d) 28,683.5 (to five significant figures)

Significant Figures: Addition & Subtraction

If addition or subtraction:

1.must have same power before addition or subtraction

2. sig. fig. in the answer is as the smaller digits after decimal point

1. 4.31 ×104

+ 3. 9×103 ( 0.39 ×104)

= 4.70 ×104(3 SF)

2. 7.4 ×103 + 0.10×103 = 7.5 ×103 (2 SF)

Significant Figures: Multiplication & Division

If multiplication or division:

1.add exponent for multiplication or subtract exponent for division

2.write the answer with the smaller sig. fig.

|

( 8.0 ×104) . |

(5.00×102) = 40×106 or 4 .0×107 |

|

|

(2 SF) |

(3 SF) (2 SF) (2SF) |

|

4.51 x 3.6666 = 16.53636 ≈ 16.5

(3 sf) (5 sf) (3 sf)

6.8 ÷ 112.04 = 0.0606926 ≈ 0.061

(2 sf) (5 sf) (2 sf)

Exact Numbers

Numbers from definitions or numbers of objects are considered to have an infinite number of significant figures

The average of three measured lengths; 6.64, 6.68 and 6.70?

6.64 + 6.68 + 6.70

3

=6.67333 = 6.67 =

RACK YOUR BRAIN

Question 1

Which of the following is an example of a physical property?

A) combustibility

B) corrosiveness

C) explosiveness

D) density

E) A and D

Question 2

Which of the following represents the greatest mass?

A) 2.0 x 103 mg

B) 10.0 dg

C) 0.0010 kg

D) 1.0 x 106 μg

Question 3

Convert 240 K and 468 K to the Celsius scale.

A) 513oC and 741oC

B) -59oC and 351oC

C) -18.3oC and 108oC

D) -33oC and 195oC

Question 4

Calculate the volume occupied by 4.50 X 102 g of gold (density = 19.3 g/cm3).

A) 23.3 cm3

B) 8.69 x 103 cm

C) 19.3 cm3

D) 450 cm3

Question 5

The melting point of bromine is -7oC. What is this melting point expressed in oF?

A) 45oF

B) -28oF

C) -13oF

D) 19oF

E) None of these is within 3oF of the correct answer.

Question 6

How many significant figures are there in the measurement 3.4080 g?

A) 6

B) 5

C) 4

D) 3

Question 7

How many significant figures should you report as the sum of 8.3801 + 2.57?

A) 3

B) 5

C) 7

D) 6

E) 4

Question 8

How many significant figures are there in the number 0.0203610 g?

A) 8

B) 7

C) 6

D) 5

Question 9

The value of 345 mm is a measure of

A) temperature

B) density

C) volume

D) distance

E) Mass

Question 10

The measurement 0.000 004 3 m, expressed correctly using scientific notation, is

A) 0.43 x 10-5 m

B) 4.3 x 10-6

C) 4.3 x 10-7

D) 4.3 x 10-5

Question 11

A laboratory technician analyzed a sample three times for percent iron and got the following results: 22.43% Fe, 24.98% Fe, and 21.02% Fe. The actual percent iron in the sample was 22.81%. The analyst's

A) precision was poor but the average result was accurate.

B) accuracy was poor but the precision was good.

C) work was only qualitative.

D) work was precise.

C and D

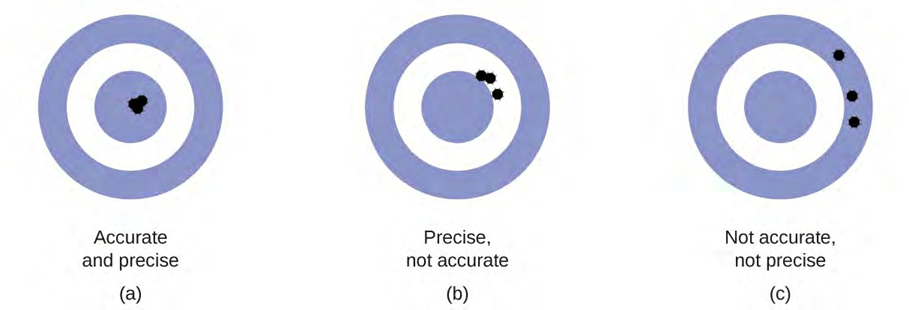

Accuracy and Precision

Scientists typically make repeated measurements of a quantity to ensure the quality of their findings and to know both the precision and the accuracy of their results. Measurements are said to be precise if they yield very similar results when repeated in the same manner. A measurement is considered accurate if it yields a result that is very close to the true or accepted value. Precise values agree with each other; accurate values agree with a true value. These characterizations can be extended to other contexts, such as the results of an archery competition.

(a) These arrows are close to both the bull’s eye and one another, so they are both accurate and precise. (b) These arrows are close to one another but not on target, so they are precise but not accurate. (c) These arrows are neither on target nor close to one another, so they are neither accurate nor precise.

Suppose a quality control chemist at a pharmaceutical company is tasked with checking the accuracy and precision of three different machines that are meant to dispense 10 ounces (296 mL) of cough syrup into storage bottles. She proceeds to use each machine to fill five bottles and then carefully determines the actual volume dispensed, obtaining the results tabulated in Considering these results, she will report that dispenser #1 is precise (values all close to one another, within a few tenths of a milliliter) but not accurate (none of the values are close to the target value of 296 mL, each being more than 10 mL too low). Results for dispenser #2 represent improved accuracy (each volume is less than 3 mL away from 296 mL) but worse precision (volumes vary by more than 4 mL). Finally, she can report that dispenser #3 is working well, dispensing cough syrup both accurately (all volumes within 0.1 mL of the target volume) and precisely (volumes differing from each other by no more than 0.2 mL).

Volume (mL) of Cough Medicine Delivered by 10-oz (296 mL) Dispensers

|

Dispenser #1 |

Dispenser #2 |

Dispenser #3 |

|

283.3 |

298.3 |

296.1 |

|

284.1 |

294.2 |

295.9 |

|

283.9 |

296.0 |

296.1 |

|

284.0 |

297.8 |

296.0 |

|

284.1 |

293.9 |

296.1 |

Mathematical Treatment of Measurement Results

It is often the case that a quantity of interest may not be easy (or even possible) to measure directly but instead must be calculated from other directly measured properties and appropriate mathematical relationships. For example, consider measuring the average speed of an athlete running sprints. This is typically accomplished by measuring the time required for the athlete to run from the starting line to the finish line, and the distance between these two lines, and then computing speed from the equation that relates these three properties:

|

time |

An Olympic-quality sprinter can run 100 m in approximately 10 s, corresponding to an average speed of

100 m

10 s

10 m/s

Note that this simple arithmetic involves dividing the numbers of each measured quantity to yield the number of the computed quantity (100/10 = 10) and likewise dividing the units of each measured quantity to yield the unit of the computed quantity (m/s = m/s). Now, consider using this same relation to predict the time required for a person.

The time can then be computed as:

running at this speed to travel a distance of 25 m. The same relation between the three properties is used, but in this case, the two quantities provided are a speed (10 m/s) and a distance (25 m). To yield the sought property, time, the equation must be rearranged appropriately:

Again, arithmetic on the numbers (25/10 = 2.5) was accompanied by the same arithmetic on the units (m/m/s = s) to yield the number and unit of the result, 2.5 s. Note that, just as for numbers, when a unit is divided by an identical unit (in this case, m/m), the result is “1”—or, as commonly phrased, the units “cancel.”

These calculations are examples of a versatile mathematical approach known as dimensional analysis (or the factor- label method). Dimensional analysis is based on this premise: the units of quantities must be subjected to the same mathematical operations as their associated numbers. This method can be applied to computations ranging from simple unit conversions to more complex, multi-step calculations involving several different quantities.

Conversion Factors and Dimensional Analysis

A ratio of two equivalent quantities expressed with different measurement units can be used as a unit conversion factor. For example, the lengths of 2.54 cm and 1 in. are equivalent (by definition), and so a unit conversion factor may be derived from the ratio,

2.54 cm (2.54 cm = 1 in.) or 2.54 cm

1 in.

Several other commonly used conversion factors are given in

Common Conversion Factors

|

Length |

Volume |

Mass |

|

1 m = 1.0936 yd |

1 L = 1.0567 qt |

1 kg = 2.2046 lb |

|

1 in. = 2.54 cm (exact) |

1 qt = 0.94635 L |

1 lb = 453.59 g |

|

1 km = 0.62137 mi |

1 ft3 = 28.317 L |

1 (avoirdupois) oz = 28.349 g |

|

1 mi = 1609.3 m |

1 tbsp = 14.787 mL |

1 (troy) oz = 31.103 g |

When we multiply a quantity (such as distance given in inches) by an appropriate unit conversion factor, we convert the quantity to an equivalent value with different units (such as distance in centimeters). For example, a basketball player’s vertical jump of 34 inches can be converted to centimeters by:

Using a Unit Conversion Factor

The mass of a competition frisbee is 125 g. Convert its mass to ounces using the unit conversion factor derived from the relationship 1 oz = 28.349 g.

Solution

If we have the conversion factor, we can determine the mass in kilograms using an equation similar the one used for converting length from inches to centimeters.

x oz = 125 g × unit conversion factor

We write the unit conversion factor in its two forms:

1 oz and 28.349 g

28.35 g 1 oz

The correct unit conversion factor is the ratio that cancels the units of grams and leaves ounces.

|

28.349 g |

|

= oz |

⎝28.349⎠

= 4.41 oz (three significant fig es)

RACK YOUR BRAIN

Convert a volume of 9.345 qt to liters.

Answer: 8.844 L

Beyond simple unit conversions, the factor-label method can be used to solve more complex problems involving computations. Regardless of the details, the basic approach is the same—all the factors involved in the calculation must be appropriately oriented to e nsure that their labels (units) will appropriately cancel and/or combine to yield the desired unit in the result. This is why it is referred to as the factor-label method. As your study of chemistry continues, you will encounter many opportunities to apply this approach.

Conversion of Temperature Units

We use the word temperature to refer to the hotness or coldness of a substance. One way we measure a change in temperature is to use the fact that most substances expand when their temperature increases and contract when their temperature decreases. The mercury or alcohol in a common glass thermometer changes its volume as the temperature changes. Because the volume of the liquid changes more than the volume of the glass, we can see the liquid expand when it gets warmer and contract when it gets cooler.

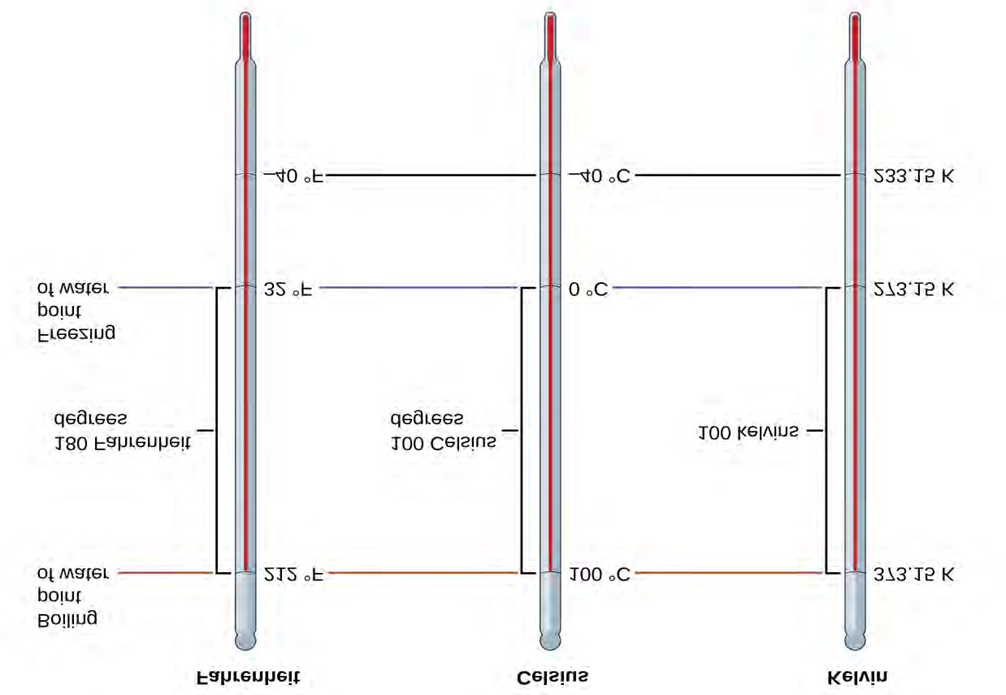

To mark a scale on a thermometer, we need a set of reference values: Two of the most commonly used are the freezing and boiling temperatures of water at a specified atmospheric pressure. On the Celsius scale, 0 °C is defined as the freezing temperature of water and 100 °C as the boiling temperature of water. The space between the two temperatures is divided into 100 equal intervals, which we call degrees. On the Fahrenheit scale, the freezing point of water is defined as 32 °F and the boiling temperature as 212 °F. The space between these two points on a Fahrenheit thermometer is divided into 180 equal parts (degrees).

Defining the Celsius and Fahrenheit temperature scales as described in the previous paragraph results in a slightly more complex relationship between temperature values on these two scales than for different units of measure for other properties.

As mentioned earlier, the SI unit of temperature is the kelvin (K). Unlike the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales, the kelvin scale is an absolute temperature scale in which 0 (zero) K corresponds to the lowest temperature that can theoretically be achieved. The early 19th-century discovery of the relationship between a gas's volume and temperature suggested that the volume of a gas would be zero at −273.15 °C. In 1848, British physicist William Thompson, who later adopted the title of Lord Kelvin, proposed an absolute temperature scale based on this concept (further treatment of this topic is provided in this text’s chapter on gases).

The freezing temperature of water on this scale is 273.15 K and its boiling temperature 373.15 K. Notice the numerical difference in these two reference temperatures is 100, the same as for the Celsius scale, and so the linear

|

°C |

TK = T°C + 273.15

T°C = TK − 273.15

The 273.15 in these equations has been determined experimentally, so it is not exact. The diagram below shows the relationship among the three temperature scales. Recall that we do not use the degree sign with temperatures on the kelvin scale.

|

|

|

RACK YOUR BRAIN Convert 80.92 °C to K and °F. |

|

⎠ |

|

⎝5 |

|

5 |

|

°F = 9°C + 32.0 = ⎛9 × 37.0⎞ + 32.0 = 66.6 + 32.0 = 98.6 °F |

|

Conversion from Celsius Normal body temperature has been commonly accepted as 37.0 °C (although it varies depending on time of day and method of measurement, as well as among individuals). What is this temperature on the kelvin scale and on the Fahrenheit scale? Solution K = °C + 273.15 = 37.0 + 273.2 = 310.2 K

|

|

Example 1.11 |

The Fahrenheit, Celsius, and kelvin temperature scales are compared.

Although the kelvin (absolute) temperature scale is the official SI temperature scale, Celsius is commonly used in many scientific contexts and is the scale of choice for nonscience contexts in almost all areas of the world. Very few countries (the U.S. and its territories, the Bahamas, Belize, Cayman Islands, and Palau) still use Fahrenheit for weather, medicine, and cook